Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico (UNM) is known for the balance and adherence to a Southwestern design identity that’s persisted throughout its 130+ years of architectural development. Upon first impression, the UNM main campus does not invoke the sense of architectural design variation that many campuses do; the modernist elements of the campus may not be initially apparent. Van Dorn Hooker, FAIA, University Architect from 1963 to 1987 and author of Only in New Mexico- An Architectural History of the University of New Mexico, decompressed the evolutionary elements of the campus’ characteristic Spanish Pueblo style and highlighted how the different stylistic and architectural choices represent a respect for the university’s unique regional heritage while also looking to the future complexities of evolving design aesthetics and contemporary technologies.

On most university campuses, the balance of institutional history and modern advancements often transform the continuity of the spaces and make it difficult to maintain a consistent sense of place. After World War II, the expansion and development of college campuses accelerated, including at UNM. In 1960, native New Mexican and UNM President (1948-1968) Tom L. Popejoy and various university parties passed the John Carl Warnecke and Associates General Development Plan, which was the first long-range development plan for campus design and development. The plan included extensive principles for campus organization, modernization, density, and the accelerated growth of enrollment. It also established university policy that new buildings would conform to the Spanish Pueblo style of architecture and that any variation would require sensitivity in design.

New Mexican architect John Gaw Meem, a proponent of the regionalist Spanish Pueblo Revival style, had a significant influence on architectural development on campus. His firm designed 25 buildings on the campus between 1933 and 1959, including Zimmerman Library, a historic structure now located at the heart of the campus.

Regional Modernism in the Evolution of Educational Design at UNM

Author

Kristen Madden

Affiliation

School of Architecture + Planning, University of New Mexico

Tags

Meem stated in the General Development Plan that:

“The University has been under pressure to abandon its established style of architecture. It has realized that in doing so, it would inevitably merge into a general stream of conformity, whereas by keeping its regional character, it possesses an individuality of appearance which belongs to it alone, a very great asset.”

With institutions around the world quickly embracing the modernist aesthetics that eschewed historical references, any new UNM projects would require a balance of modernity and regional respect.

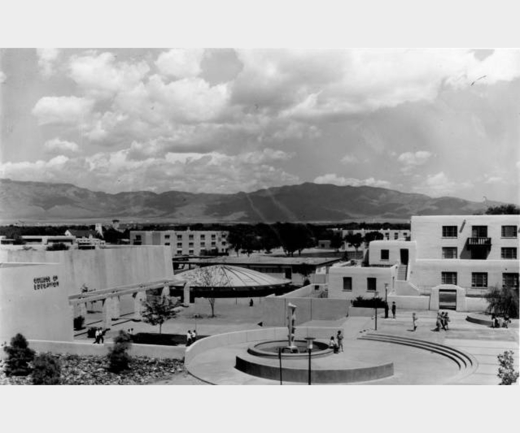

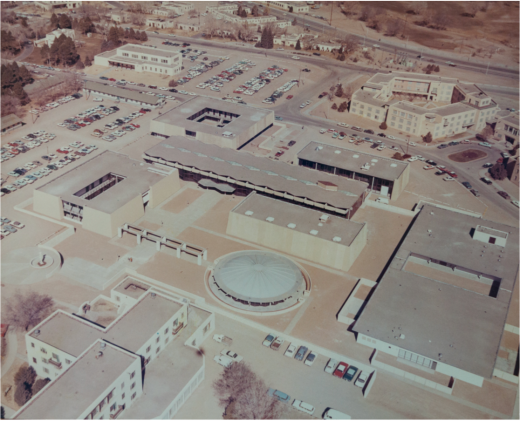

UNM campus development over the next 25 years achieved varying amounts of success with regionalist design while acknowledging the necessity of modernism to stay progressive as a growing educational institution. One of the first challenges of achieving this modern regionalism came with the development of The College of Education Complex (2). This was the first UNM project for which a detailed program was written, and Popejoy appointed a committee and Don P. Schlegel, FAIA, of the School of Architecture to be a liaison between the architect and the university. The firm Flatow, Moore, Bryan, and Fairburn was selected, with Max Flatow as the partner in charge of the project. No other complex of buildings since Meem’s work in the 1930’s has had such a decisive impact in shaping campus structures that succeeded them.

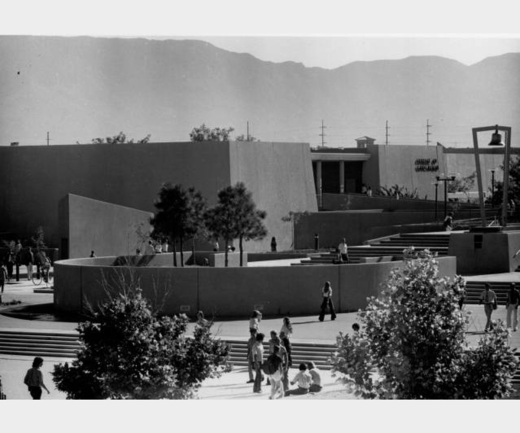

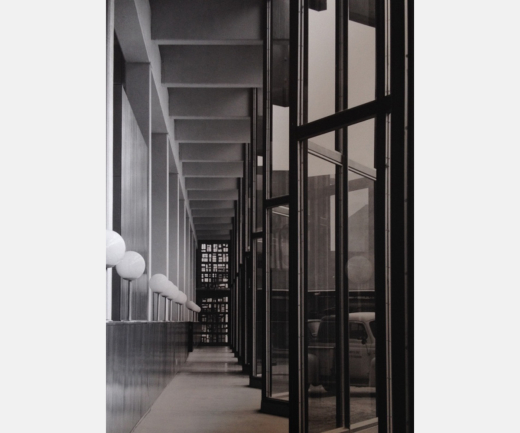

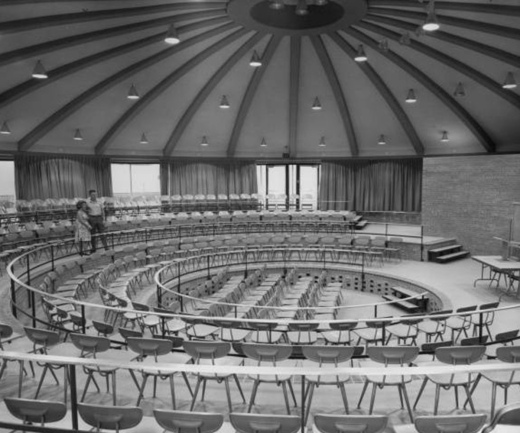

Flatow’s firm’s design proposed separate buildings with different functions inside a semi-enclosed complex that was compared to the pueblo ruins at Coronado State Monument on the banks of the Rio Grande River outside of Albuquerque. Buildings included the round Kiva Auditorium, Travelstead Hall, a classroom building, Masley Hall, Simpson Hall, and the Manzanita Center. The proposal included massive, sloping precast concrete walls that formed the fortress-like exterior, meant to evoke the massive, battered walls of Spanish Pueblo Revival. The interior of the complex used a modernist aesthetic with metal curtain walls either faced into courtyards or end walls. Other features included Double-T precast concrete panels, round concrete columns, two-way concrete slabs, and other new construction techniques and building programming that embraced modern design and technologies, a first on the campus. When the College of Education moved into their new facility in 1963, it was hailed as an “architectural milestone,” while others felt it departed too far from the traditional Pueblo Revival aesthetic.

Travelstead Hall, which housed the library and administration functions, featured floor-to-ceiling glass on the north and south walls with simple, zigzagged panels shaded by precast concrete panels. The roof was constructed of precast concrete beams and deck, a popular roof style of the 1960s that were placed in a way that created diamond-shaped skylights. A passageway featured a stained glass wall designed by art professor John Tatschl, and for the first time in many years, a significant amount of artwork was incorporated into a campus design. Edith Cherry, a longtime architect, UNM professor emerita, and former School of Architecture Director expressed that this design work demonstrated that both Modernism and Regionalism could be represented at the same time, a feat that very few other campuses in the United States had even attempted, let alone done successfully at that time.

While the Kiva Auditorium, shaped for the ancient Kivas of the pueblos in New Mexico, had immediate issues with heat gain from the sun shining through the glass curtain walls, corrective alterations were made and most of the remaining complex survives predominantly unaltered. The College of Education complex was an experiment in melding the principles and technologies of the Modern Movement, while paying a deep respect to the design elements of traditional New Mexican architectural style without using it as merely a cliché ornamental afterthought, an issue that arises to varying degrees in Southwest design. Flatow, Moore, Bryan, and Fairburn went on to design or expand several other buildings on campus and received national attention when they won several awards for their ability to embrace International Style modernist principles and incorporate abstracted regionalism into traditional design requirements.

During this transformative time on campus, the College of Education wasn’t only the architectural design that was pushing the boundaries. Gone were the days where the university could accommodate the enrollment numbers, the ongoing construction, and the vehicular nature of the design of campus. Alongside the 1960’s General Development Plan, in 1962 a landscape plan was prepared by Garrett Eckbo, a nationally prominent landscape architect of the firm Eckbo, Dean, and Williams, for the central part of main campus. A park-like pedestrian area with a pond was planned between the Administration Building and Zimmerman Library, extending through various other corridors on campus that had previously been vehicular circulation and creating the popular modernist idea at the time of “streets to malls”.

Similarly, to the more adventitious architecture being built at this time, there was pushback by some on the move away from the Pueblo Revival Style and regional context of the planning and landscape design. The next 25 years eventually led to the implementation of the proposed Eckbo landscape and planning which was conducted by Guy Robert “Bob” Johns, ASLA. This would eventually come to be the design of Smith Plaza, along with several other pedestrian malls designed by various architects. However, the most controversial and ultimately the most successful addition was the Duck Pond, designed by Eckbo and completed in 1976.

Eckbo at the time was known for his then-revolutionary idea that, “Gardens are places in which people live out of doors.” This idea invited organization of outdoor spaces that are not only inviting and open, but entertaining and easy to maintain. While this is similar in notion to UNM’s General Development Plan, the emphasis of Eckbo’s design on open land, low density, and regionalism was not initially welcomed by many critics. There was hesitation over water features, including rolling mounds of earth, a recirculating waterfall, and lush landscaping, in the arid environment of New Mexico. Even with adjustments made for more environmentally appropriate landscaping, the editor of the Daily Lobo at the time described it as “a new height of tackiness and inappropriate for the campus.” When it was completed, students flocked to the new pond and its surrounding landscape. The Duck Pond has become not only a campus fixture, but also a public attraction in the city of Albuquerque and one of the most successful modern additions to the UNM campus.

In 1969, a headline in the Santa Fe New Mexican read, “University Landmark Falls before Progress,” when the Zimmerman Stadium was demolished on the central campus across from the Zimmerman Library. Throughout the 1970s, progressive and sometimes controversial modern architecture was added to the space under the context of design called Regional Modernism/Contemporary, also sharing characteristics of Brutalism. The Faculty Office and Classrooms, later known as Ortega Hall, was completed near central campus in 1971 by the architectural firm Ferguson, Stevens, Mallory, and Pearl. The original design had elements of brick as a palette, with a second-level deck that overhung the first floor, giving the illusion of a floating mass. While this was a defining element of many modern designs of the time, it was not within the standards that had been set forth within the Pueblo Revival and Regionalism style. Ultimately, the plan submitted by George Clayton Pearl had to be reworked so that precast concrete panels were added around the bottom floor of the building to better align with the regional design elements and massing, echoing the thick adobe walls of the Pueblo Revival style. The addition of these panels was said to create unpleasantly dark spaces in the hallways and destroyed the design concept.

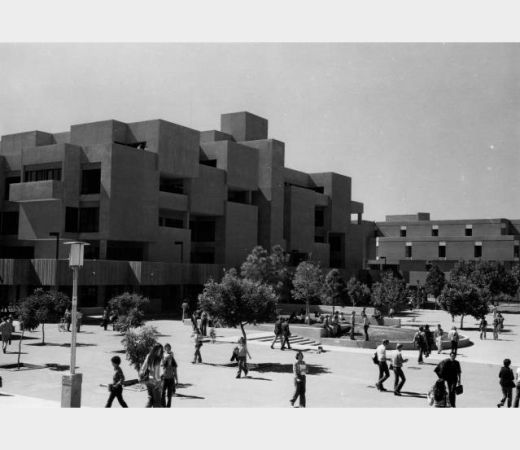

Another Regional Modern/Contemporary structure built in the place of the old Zimmerman Stadium was the Humanities Building. Completed in 1974 by architectural firm W.C. Kruger and Associates, the Humanities Building was inspired by the additive massing of Pueblo villages. Classroom masses protrude from the solid framework of the building and create variations in proportions that play off solids and voids. The shadows, colors, and an absence of complete symmetry align with a Pueblo Revival composition, but at the same time add the contemporary element of geometric complexity. For example, the building was constructed of contemporary materials such as concrete cubic forms, but they were encased in beige plaster.

Despite the strong influence of the Pueblo Revival regional aesthetic in New Mexico in general and specifically on the University of New Mexico’s campus, the impact that the Modern Movement has had on the campus’ built environment cannot be denied. Looking at the present-day campus, one can appreciate this in later construction, especially George Pearl Hall. Designed by Antoine Predock in 2007, who once was a student on UNM’s campus, George Pearl Hall emulates how past campus designers combined existing palettes, materials, and massing with the most contemporary techniques in design. The structure is also a teaching tool for the School of Architecture and Planning that occupies it. Architecturally, the UNM campus is an outstanding example of what comes from diligent and genuine consideration of how to pay homage to the past while understanding the necessity to move forward design-wise in a modern Southwestern civilization.

Special thanks to Edie Cherry for sharing her profound depth of knowledge about the University of New Mexico architecture and design.

Sources

Hooker, Van Dorn, Only in New Mexico: An Architectural History of the University of New Mexico. The First Century, 1889-1989, University of New Mexico Press, 2000.

The Guide to New Mexico Architecture: UNM Central Campus

Albuquerque Modernism: A Guide to Mid-Century Architecture in Albuquerque, New Mexico

About the Author

Kristen Madden is a graduate student currently in her final semester of study at the School of Architecture + Planning, University of New Mexico. She is a freelance Intern Architect & Historic Preservation & Regionalist Advisor, and currently lives and practices in her hometown of Albuquerque, New Mexico. After living in various states across the southwest region of the United States for 15 years, she hopes to bring appreciation and recognition to the current and past regional architectural accomplishments of her hometown.

Modern ABQ is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas,

Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, South Dakota, and Vermont. Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting Docomomo US as a member or make a donation so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.

Sunbelt Modern Part Four

Engineering a Legacy: Sergio Acosta Remembered