Albuquerque's modernist architecture, spanning the pre-war period into today, has only recently begun to be recognized and contextualized for the roles it has played in the city's development. The city government commissioned its first survey of mid-century modern architectural resources in 2013, followed closely thereafter by the study of select structures by a UNM architecture class. As interest has grown, new resources and research have emerged from a growing group of enthusiasts, preservationists, architects, and historians. Residents, tourists, and even fans of the many programs filmed in Albuquerque have begun to appreciate the style, story, and scope of the buildings that dot the city's built environment.

Located in Central New Mexico, Albuquerque's mid-century past and high desert climate provided an incubator for innovative ideas and approaches to architecture, some merging traditional materials and regional practices with the principles of modernism. Following World War II, the city doubled in population. The expansion eastwards created opportunities for the use of new materials, construction methods, and architectural problem-solving. Today, the city is home to a widely recognized School of Architecture and Planning and boasts a flourishing inventory of residential, commercial, and institutional modern structures.

Thank you to Modern Albuquerque, Thea Haver, Ethan Aronson, Nick Roth, and Kristen Madden for their contributions to this Regional Spotlight.

Sunbelt Modern Part One

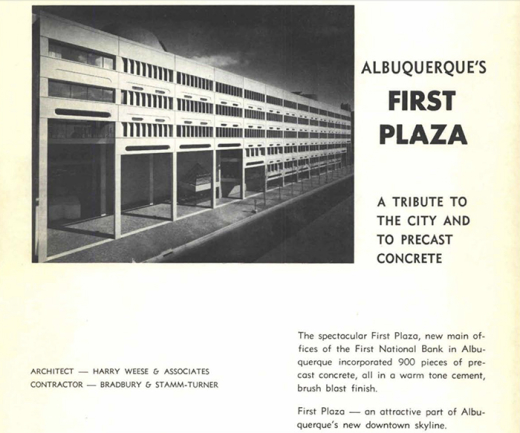

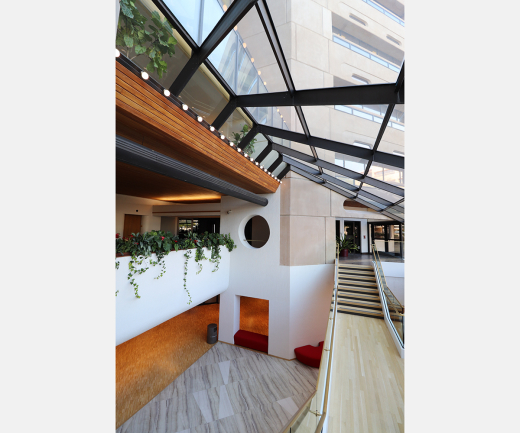

Inside the Weese-designed First Plaza Building

by Thea Haver

Albuquerque’s diverse architectural landscape may be most evident in its downtown corridor, where urban renewal projects are starkly juxtaposed with the city’s railroad past. A notable example is the First Plaza building. Considered the “premier building of the southwest” by more than just its owners, the landmark was designed by Modernist master Harry Weese. The project was funded and developed by First National Bank on a site initially considered for City Hall. Arthur Cinader, chairing the project for the bank, sought out “the best” designer for their money.