This Docomomo US Regional Spotlight article offers some historic background and insight on a key contribution by Hawaiian modern architect Vladimir Ossipoff (1907-1998). In general, Ossipoff’s architecture consistently fused the climate, topography and culture of Hawai‘i like no other over his over 6 decades of practice solely in the islands. His design sensibility was timeless, elegant and usually understated.

For me, Ossipoff’s transformation of the lanai – a Polynesian veranda – into modern building form which evolved over several decades and various projects is a story worth retelling. By mid-century, the modernized lanai distinguished residential architecture in Hawai‘i from that of the U.S. mainland, however, it was Ossipoff who transformed it into a distinct building type at the civic scale.

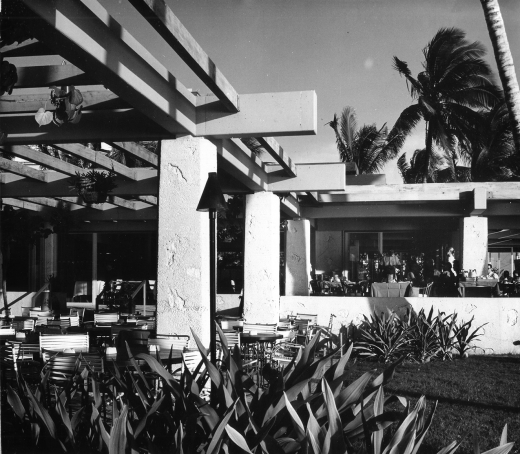

As I previously wrote in the essay The Living Lanai, the Blanche Hill House (1961) may have been Ossipoff’s first realized lanai building; the Outrigger Canoe Club on Waikiki Beach (1964) perfected this building form; and the Arrivals and Departures Terminal at the Honolulu International Airport (renamed Daniel K. Inouye International Airport in 2017, 1970-1978) was his grandest realization of such.(1) Still in use today, this building is Ossipoff’s most important and high profile civic commission, but is not his best for many reasons beyond his control. However, I believe that its experiential virtues and cultural value is often overlooked by its owner, the State of Hawai‘i and even many modern architecture aficionados.

Ultimately, the Honolulu airport terminal’s function as the gateway to the Aloha State transcends its architectural glory. With this in mind, this story is limited to my perspective as an architect with one eye to the past and another toward the future.

Vladimir Ossipoff’s Grand Lanai at Honolulu International Airport

Author

Dean Sakamoto, FAIA

Affiliation

Docomomo US/Hawaii

Tags

A Native Concept

The lanai was a common aspect of the native Hawaiian hale or dwelling complex for daily life, social gatherings, and spiritual ceremonies—all of which took place outdoors—the lanai was a freestanding, open-sided, post-and-beam wood frame with a roof of thatch or dried leaves.(2) This rudimentary shelter remains prevalent along island shores, especially where the thick and sinuous hau, an indigenous climbing plant, provides a living canopy that usually outlives its supporting timber structure. The legendary Hau Tree Lanai, which was originally an adjunct structure to a modest hotel of the same name on Waikīkī Beach in the early twentieth century, was typical of this primordial structure.(3) Early Western settlers adapted the model to serve as an extension to houses and buildings, supplementing the interior space but remaining open to the breeze and protected from the rain.

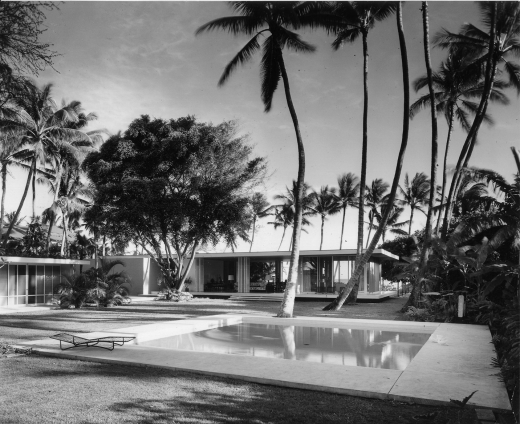

In addition to architects, for island image makers, the lanai was central to Hawai‘i’s modern architectural identity. On the domestic scale, the lanai was the defining feature of the “environmental home” that provides the ideal means of protection from the weather and multipurpose space for daily living and social functions.(4) As such, the lanai could replace the family room. From the 1950s onward architects, journalists, and institutions seeking to popularize the virtues of island life pointed to the lanai as proof of modern culture’s capacity for gracious indoor-outdoor living. The novelty of this design and usage was highlighted in a feature story on one of Ossipoff’s houses in Sunset magazine. A photograph of an Ossipoff designed lanai appears on the cover of the September 1976 issue, with the cover line for the lead article: “Hawai`i’s Lanai Idea—The Room with the Missing Wall.” Based on a form of shelter specific to its climate and place, Ossipoff’s reinterpretation of lanai as a building is simultaneously universal, local, historical and uniquely modern.

Through his residential work during this period, Ossipoff explored the possibility of the lanai as a total structure—beyond the habitable veranda that was also referred to as a lanai. His purpose in reinterpreting the original lanai form was not to resurrect or mimic native architecture or a self-conscious theoretical invention.(5) Ossipoff’s designs grew out of practical problem solving in relation to his clients’ requirements and site conditions. He also drew on local architectural precedents that he believed had stood the test of time.

For example, Ossipoff directed his designers to study the elements of civic structures in Honolulu built in the 1920s and 1930s of local stone and imported cement. The arbors at Ala Moana Beach Park, designed by Harry Sims Bent in the 1930s under City Parks Board chairman Lester McCoy, provided an example of functional aesthetics that would inform later lanai innovations.

The lanai is thus a “non-building” structured by a grid of columns that carry either a low flat roof or an armature of exposed girders and beams overhead. The lanai building blends and harmonizes with existing topography, plant life, and setting; it is a structure of voids that highlights and frames views through and around it. Unlike Ossipoff’s most robust regionally distinct structures—such as the IBM Building and the iconic Robert Shipman Thurston, Jr., Memorial Chapel at Punahou School, which are more physically imposing and not as spatially porous—the lanai building is less an architectural object than a structural framework to be experienced before it can be fully understood.

Honolulu International Airport: A Grand Lanai Forgotten?

Ossipoff’s appointment as the principal designer for the modernization of the Honolulu International Airport in anticipation of rapid advances in aviation technology was no accident. Despite being a registered Republican in a new Democratic state, Ossipoff was hand-picked for this job by the then director of the State Department of Transportation, Fujio Matsuda. Matsuda, a MIT-educated engineer with a doctorate degree, was asked by the liberal Governor John A. Burns…“who is Hawai’i’s best architect?” The young director replied “Vladimir Ossipoff, Governor.”(6)

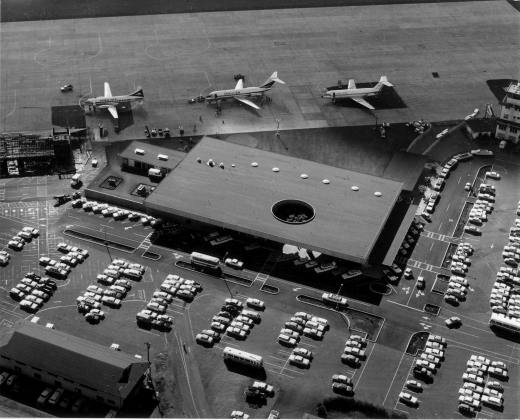

This recommendation confirmed his status as Hawai`i’s top architect and allowed him to adapt his lanai concept to a large-scale building with restrictive design needs. His initial assignment in 1970 was to improve the existing John Rodgers Terminal, which had been designed by the local architect Theodore Vierra (1902-1987) and completed just seven years prior. The Rodgers Terminal had been obsolete almost as soon as it opened. Within a year of its completion, Boeing announced the imminent production of its 747 jumbo jet, which would require two-story departure gates and larger runways than the “new” airport provided. Soon after, Pan American World Airways announced plans for a regular jumbo jet flights to Honolulu. State funds were appropriated almost immediately.

The success of the Kahului Airport Terminal on Maui, completed in 1966, also qualified Ossipoff to be the lead design architect for the modernization of Honolulu International Airport. (7) To many, this was the most prestigious design commission in the state aside from the new State Capitol, designed by John Carl Warnecke and Associates (1969), which was then under construction.

The project’s limited time frame and specific and complex program requirements created a challenge for the architectural and engineering team. Ossipoff was required to begin planning immediately following a tour of twelve recently completed airports in North America, including Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, Virginia, and the TWA Terminal at John F. Kennedy Airport, both designed by Eero Saarinen (1910-1961). As a result, multiple firms were contracted to implement specialized design and planning tasks for the new jet, which has twice the passenger and baggage capacity of the older 707.(8) Working under the Ralph M. Parsons Company, which was responsible for the planning and construction programs, and the airport consultant Leigh Fisher of San Francisco, Ossipoff’s firm teamed with Sam Chang Architects and Associates, also based in Honolulu, in a joint-venture agreement. The size of the Honolulu airport commission and Chang’s proven ability to handle complex projects helped state officials justify their selection of the design team. The Ossipoff-Chang team was responsible for renovating the central ticketing lobby, the arrival and departure terminal, baggage handling facilities, and multiple passenger-holding areas. During its eight-year involvement, Ossipoff’s firm also contributed designs for new facilities including an international ticketing and terminal extension, and a new central concourse built over the original one-story structure around an existing garden, which forms the heart of the airport.

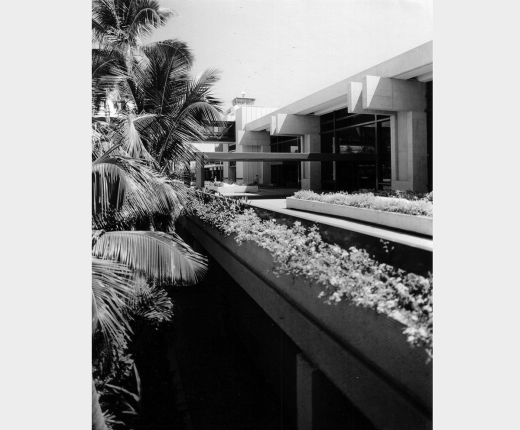

Ossipoff designed a permeable, bold, yet flexible and graceful structure that incorporated as many openings at its perimeter and ground planes as possible—with the exception of the ground-floor baggage claim area, there is no air-conditioning in the public areas of the ticketing and terminal departures lobby. His basic scheme raised Vierra’s terminal around the existing control tower to two stories, creating long bar-like structures fronted by new elevated passenger drop-off ramp at the second-floor departures ticketing area and the arrivals baggage-claim area below it. A series of open light wells divides the elevated passenger drop-off roadway from the two-story departures terminal and curbside drop-off canopy structure. This is a distinctive aspect of the design: palm trees spring from light wells between the departures terminal and roadway, and light and air are brought to the baggage and pickup area at the lower level. The terminal and roadway are linked by covered bridges. The intimate scale and shade of the bridges contrast with the large terminal facility, which, according to Ossipoff’s original design proposal, was to be illuminated naturally by continuous skylights running between the long-spanning beams in the terminal’s ceiling. This bold concept was not realized: only a few skylights from Vierra’s earlier hangar-like structure were retained, in the ceilings of Ossipoff’s renovated ticketing halls. Ossipoff’s linear plan allowed later expansions of the terminal to the east and west (executed by others).

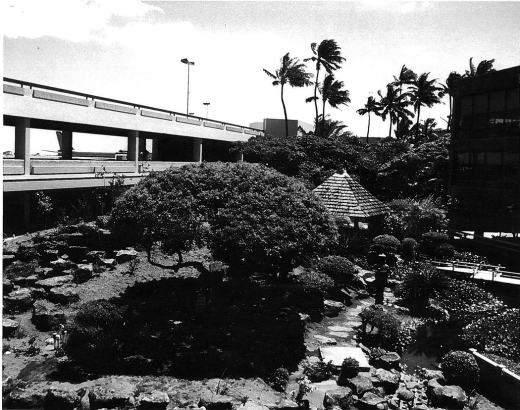

Of the several elements remaining from the Rodgers Terminal layout, the lush, landscaped garden dedicated to the founder of the Republic of China, Dr. Sun Yat-Sen reinforces Ossipoff’s design. The garden was designed by Richard Tongg (1900-1988) — one of the islands’ leading landscape architects and a frequent collaborator of Ossipoff’s — and completed in 1963. It is located in the triangular open space created by a Y-shaped structure (designed by Vierra) that contains bridges overlooking the garden and originally, an open-air platform above the runway that allows a view of aircraft taking off and landing.

Working with Vierra’s footprint, the Ossipoff office designed the new Central Concourse, to create a series of larger and higher enclosed passenger gates and holding areas to accommodate the new aircraft. Although the gate–holding areas are under roof, Ossipoff’s team recognized the genius of the Vierra-Tongg design and kept the sides of the covered concourse open to the garden within it. The Central Concourse and passenger holding area were Ossipoff’s final contributions to the airport project.

Tongg’s garden, which was near its maturity when Ossipoff encountered it, creates a condensed paradise of meandering paths that lead through varied tropical foliage, ponds, and a gazebo monument. The inclusion of the garden intensifies the lanai experience: it presents travelers with the beauty and variety of the Hawaiian landscape upon their arrival after a plane ride of five hours or more.

Ossipoff designed the exterior of the airport complex to be as open as possible. The land side of the terminal faces mauka (toward the mountains) and thus is exposed to trade winds and their accompanying showers; it is in-filled with fixed glass panels and high vertical glass jalousies for ventilation and protection from the rain. The low-canopied entry portals to the bridge connections are wide open, without doors, providing access to the ample cooling trade winds.

Rain is kept from entering the terminal portals by the low flat canopy roofs that are continuous from the bridges to the drop-off structures. Another set of high glass jalousies in the walls, behind the makai (ocean facing) ticket counters opposite the entry portals, allow upward cross-ventilation and can be closed against wind-driven rain. In anticipation of the less frequent balmy kona (from the south) winds, Ossipoff proposed a supplemental fan system to move air across the terminal in the opposite direction to mimic the trade winds; however, the system was not implemented.(9)

Despite the functional constraints on the Honolulu airport design, the Ossipoff team was able to transfer several ideas developed in two earlier projects. In both the Outrigger Canoe Club and the Kahului Airport Terminal, the Ossipoff firm established formal, structural, and climatic concepts that shaped the modernized Honolulu International Airport. The Ossipoff half of the airport joint-venture office was led by Franklin Gray, who had already worked for Ossipoff for more than eight years. According to Gray, he was given near-total design responsibility; the only requirement Ossipoff imposed was “to keep it open, no air-conditioning.”(10)

Because Gray had worked on the Outrigger Club just a few years earlier, his initial design strategy on the airport project was to emulate the lanai-like qualities and structural principles of the smaller club complex at a larger scale. Like those at Outrigger, the new airport structures typically consist of post-and-beam reinforced-concrete frames with massive, textured vertical supporting piers. Spatial transitions between the structures are covered by low, flat roofs, and daylight spills through gaps between overlapping roofs and through high glass jalousie windows. Compared with the much smaller club, the airport gave Ossipoff less latitude to fully execute his preferred spatial dynamics. Instead, he focused on designing clear passenger circulation routes that are punctuated with episodes of daylight and foliage throughout.

The materials Ossipoff used in the new airport created a distinctly modern and Hawaiian sensibility that harmonized with the heavily planted gardens, O‘ahu island’s verdant Ko‘olau mountain range, and the bright, cloud-filled sky. The native koa wood veneer on the interior soffits and ticket counters and the intricate bush-hammered concrete are handsome and sensuously Polynesian in feel. According to Gray, the bush-hammered finish is an original variation of the architect Paul Rudolph’s signature “corduroy concrete,” first used at the Yale Art and Architecture building (1963). Instead of using fluted form boards, the Ossipoff team specified a less expensive method of detailing: nails were driven into the wood form boards in vertical rows, creating a finer and more varied pattern that did not require hammering off the excess fluting. The polished terrazzo floor and a decorative screen above the length of the central ticketing counters enhance this effect. The screen, titled ‘Opinalu (bend of a wave), is an abstract relief grillwork designed by the Ossipoff office, seven feet high by two hundred feet wide and made of milled vertical redwood. Because it is positioned against jalousie windows, it admits air and light, supporting the environmental porosity of Ossipoff’s lanai concept while evoking an image of the ocean whose waves brought the first Polynesians settlers, and later, Western adventurers to Hawai‘i’s shores.

It was through the evolution of the lanai that Ossipoff contributed most profoundly to the Hawaiian built environment. By combining the logic of an indigenous vernacular typology, twentieth-century modern precedents, and a Japanese sensitivity toward nature, he established a timeless and original building form possible only in the tropics. But the fate of this building type remains to be determined, as does that of other surviving buildings designed by Ossipoff.

In the early 1980s, the Blanche Hill House was demolished by speculators; the Outrigger Canoe Club’s design integrity was spared from a controversial renovation in the early 2000s; and over the past decade, the Honolulu International Airport has been subject to a modernization program that lacks the understated elegance, spatial choreography and the clever natural ventilation strategies devised by the Russian-American master.

Even before Ossipoff’s death in 1998, the bold and finely proportioned concrete portals of the Arrivals and Departures Terminal were compromised. Beginning with a series of incompatibly scaled hip roof metal and glass canopies dropped in over the original departures level forecourt. More recently, Ossipoff’s subtle, long and low-slung curb-side canopy that once bridged over an equally long light well to the arrivals terminal below, is now replaced by an extroverted upturned version. While the glass canopies may have been a practical measure to provide weather protection for departing tour groups, its incongruous design is a mute response to the original architectural intention.

Ossipoff choreographed the departure sequence from the automobile drop-off lane to the low, covered entry (where lei and embraces are exchanged) to the open and breezy transitional forecourt, then into the high-ceiling sheltered ticketing area. In retrospect, Ossipoff’s grand airport-lanai sought to humanize the process of air travel by designing not just a building, but how one experiences it. His scripted approach paid attention to how people communed with both themselves and with the elements of nature.

Today, as the Hawai‘i State Department of Transportation-Airports continues its 21st century modernization to its primary facility (with federal infrastructure funding), one wonders if Ossipoff’s lanai concept is still relevant and even understood.

In closing, I’d like to pose a few broader questions and a wish for the future. What lessons can be learned from Ossipoff’s timeless incorporation of native wisdom, modern aesthetics and design problem solving today? Can contemporary architecture’s integration of the built and natural environments take on a regenerative function and yield greater ecological, economic and human benefits that exceed its environmental cost? What design innovations unique to Hawai‘i will its next generation of clients, architects and historians preserve and advance?

Finally, I hope that what we learned from Vladimir Ossipoff’s architecture will continue to evolve – not just replicated – right here in the mid-Pacific, where the humble lanai got its name.

Notes

1. Dean Sakamoto, Karla Britton, et al, Hawaiian Modern: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff, (New Haven and Honolulu: Yale University Press in Association with the Honolulu Museum of Art, 2007, 2015, 2022), 93-106.

2. Te Rangi Hiroa [Peter H. Buck], Arts and Crafts of Hawai`i, vol. 2, Houses (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1957; rpt., 1964), 100. The indigenous Hawaiian lanai was typically an adjunct to the native dwelling complex, called a hale. The hale usually consisted of a hale noho, a thatched windowless sleeping hut, and a halau, a thatched longhouse with at least one open end. Hiroa was the director of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu from 1936 to 1951 and wrote a multivolume manuscript on the arts and crafts of Hawai`i, which was first published in 1957, about the time a reconstructed hale went on display in the museum.

3. Don Hibbard and David Franzen, The View from Diamond Head: Royal Residence to Urban Resort (Honolulu: Editions Limited, 1986), 68–70.

4. Harry Seckel, Hawaiian Residential Architecture, exhibition brochure (Honolulu: Bishop Museum, 1954). Seckel defines the Environmental Home for Hawai`i: “These homes are a departure from the concept of the enclosed house as an entity separate from its surroundings. Instead, the entire site is considered as the dwelling. Some parts of it are completely open to the elements and others have the various degrees of protection required. Outdoor and indoor spaces are unified rather than separated. There are fewer walls, and more glass than the conventional house. Protection from wind and sun is carefully worked out in these homes. In fact, in many respects they constitute better than standard shelter in spite of their extreme openness” (11).

5. Robert Griffing, Jr., “Lanai Exhibition, Honolulu Academy of Art,” manuscript, 1949, Honolulu Academy of Arts Archives.

6. Dean Sakamoto, conversation in Honolulu (2004) with Dr. Fujio “Fudge” Matsuda (1925-2020). Following his career in private practice and state government, Matsuda became the President of the University of Hawai‘i, 1974-1984.

7. Dean Sakamoto, conversation with Sidney Snyder, Jr., Honolulu, Nov. 10, 2006. The lanai concept at Kahului was developed by Ossipoff and Snyder; Snyder was the lead designer on the job. According to Snyder, the open-air floor plan, carefully oriented for protection from the trade winds, and the circular opening to the sky were two ideas that they agreed upon easily. However, Snyder credited Ossipoff with the more eccentric detailing and materials, such as the elliptical coffers and the walls made of stacked local river stone. 8. Ben Schlapak, “A History of Hawai`i’s Airports and Related Aviation Milestones,” manuscript, undated, Hawai`i State Department of Transportation–Airports, Honolulu.

9. Dean Sakamoto, conversation with Franklin Gray, Honolulu, Nov. 7, 2006. Ultimately, only the lower-level baggage areas were air-conditioned in Ossipoff’s design.

10. Ibid

About the Author

Dean Sakamoto, FAIA, is the Principal of Dean Sakamoto Architects and founder of the SHADE group (Sustainable Humanitarian Architecture Design for the Earth), based in Honolulu, Hawaii. Mr. Sakamoto is an educator and practicing architect with a national presence and diverse local expertise. As an educator, he served on the faculty of the Yale University School of Architecture and is currently a lecturer at the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and associate affiliate faculty at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning. His New Haven and Honolulu based firm, Dean Sakamoto Architects, is known for its environmentally sensitive and culturally specific designs. He is the architect of the Juliet Rice Wichman Botanical Research Center at the National Tropical Botanical Garden on Kauai, Hawaii, a LEED Gold certified and hurricane resilient building and recipient of the 2010 American Institute of Architects (AIA) Honolulu Award of Excellence. Mr. Sakamoto currently serves on the AIA National Advisory Committee on Resilience and is the lead developer of HURRIPLAN: Resilient Building Design for Coastal Communities, a Federal Emergency Management Agency certified professional training program offered at the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center. Mr. Sakamoto earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Oregon, a master’s degree in architecture from Cranbrook Academy of Art, and a master’s degree in environmental design from Yale University.

Sunny Spotlight: Modernism in Hawaii is part of the Docomomo US Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, South Dakota, Vermont, and Albuquerque. View all Regional Spotlights here.

Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting Docomomo US as a member or make a donation so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.