The Other Las Vegas Part Two

Jones and Emmons: Modernism for the Masses

by Dave Cornoyer

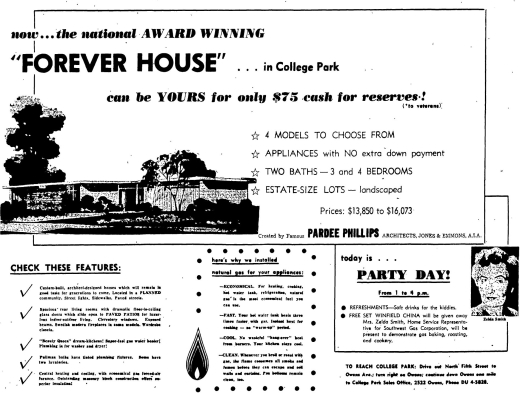

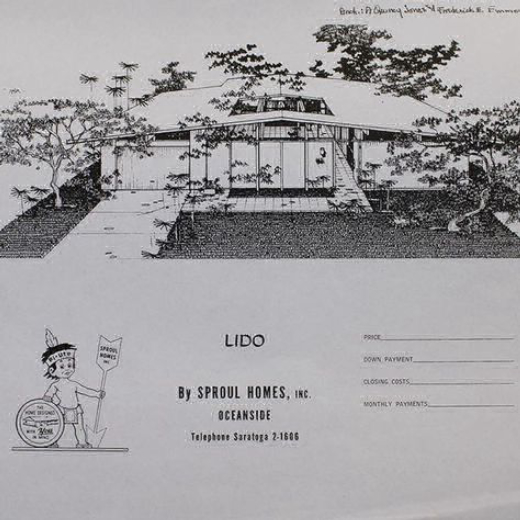

Architects A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons made a successful name for themselves in the midcentury era as the preferred architects for prolific developer Joseph Eichler. While not exclusively employed by Eichler, it was their work with another well-known West Coast builder that would first bring them to the Las Vegas market. Builder George Pardee Sr. originated his construction company in 1921, later forming the Pardee Construction Company in 1946 with sons Hoyt and George in 1946, son Douglas in 1948 and finally financier Gifford Phillips in the 1950s, at which point the company became Pardee-Phillips. Pardee-Phillips originated the concept of the ‘Forever Home’ in 1952 with the development of their first large-scale residential subdivision tract, Southdown Estates, in Pacific Palisades, California, for which Jones and Emmons were hired as the designers.

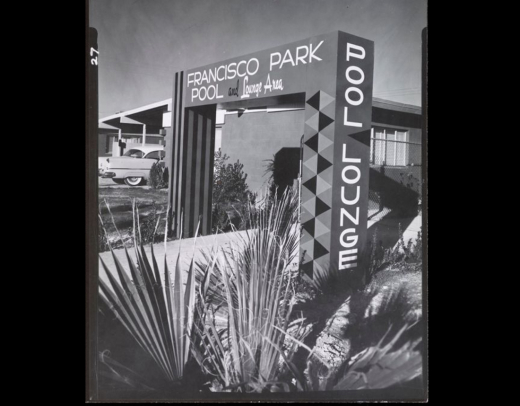

The idea of the Forever Home was to buck traditional-style construction, decrease maintenance, and was allow for do-it-yourself upkeep with designs that were termite-proof, rot-proof, fuel saving and laden with smart insulation features. Pardee-Phillips entered the Las Vegas market in 1953 with the purchase of a tract of land near Maryland Parkway and San Francisco (Sahara Avenue) Street. The tract was selected for its proximity to growing residential areas, schools, churches, and retail amenities. The new community would come to be known as Francisco Park.

Local architects Walter Zick and Harris Sharp (Zick & Sharp) were brought in to direct the planning and development. Their brief included considerations for safeguarding children from heavy traffic and overall guidance and integration of the community research conclusions addressing specific issues the area faced. Sharp, was reported to be in a favorable condition to advise on these needs, as he was a city commissioner at the time.

Pardee-Phillips commissioned research funds following a conference of engineers, architects, economists, consumer representatives, bankers, and company officials who explored the possibilities of translating scientific home engineering and family finance into practical benefits to small property owners. The results were that this new community was to be composed entirely of duplexes. The reasoning being that in the past, prospective homeowners had to face years of slow amortization payments entirely paid out of wages or salaries. Economists at the research conference concluded that most families would do better budget-wise with a dual-purpose dwelling that would provide both a home unit and an income-producing unit.