Think of Vermont, and what comes to mind? Most likely a decidedly nostalgic vision of quaint villages, white churches with tall steeples, picturesque farmsteads with red barns and cows grazing in green fields, and covered bridges crossing meandering rivers. This is all true, but it’s not the complete story. Believe it or not, the 20th century did happen in Vermont and left its own unique imprint on our built environment. For the past 15 years I have been researching and documenting Vermont’s modernist architectural heritage, a task that continues today and never ceases to reveal new discoveries. What draws me to this topic is that it’s a challenge; if you’re interested in seeing examples of Federal, Greek Revival, Italianate, and Queen Anne buildings, these can be found on Main Street in most Vermont towns. But if you’re looking for Usonian, International Style, Contemporary, Shed, A-Frame, and other modern-style buildings they’re here too, but they’re just not as obvious. They’re tucked away on mountainsides or in small clusters on the edges of older neighborhoods. You must look for these buildings, and once you start seeing them, it quickly becomes clear that Vermont has a lot to offer in terms of 20th-century architecture and design. The following articles are just scratching the surface of Vermont’s modernist heritage, and I’m grateful to the contributors for taking the time to share what they have discovered with you. Hopefully, after reading these articles, you’ll add a modernist building or two to your mental image of the Green Mountain State.

-Devin Coleman, State Architectural Historian

Green Mountain Modern Part One: The Charterhouse of The Transfiguration; Vermont’s Granite Monastery

by Rebecca Lo Presti

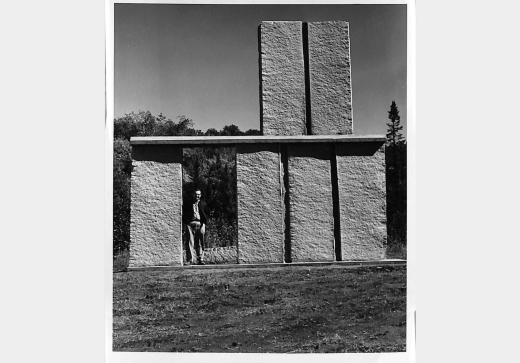

In Vermont’s Mount Equinox resides a granite monastery, orchestrated by modern architect Victor Christ-Janer. The material, location, and design make the Charterhouse a uniquely intriguing example of modernism in Vermont, especially because little has been written about the monastery.

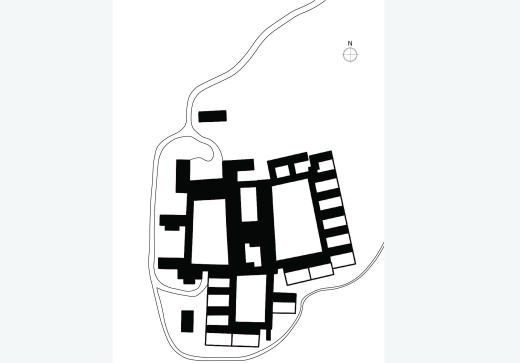

The Charterhouse of Transfiguration is a modern monolith of granite, hidden away in the valley of Mount Equinox in the southwestern corner of Vermont. The residents of the utilitarian Charterhouse are monks belonging to the Carthusian Order- a sect of Catholicism that thrives on seclusion. Despite its isolation, though, the Charterhouse of Transfiguration is a fascinating- and understudied- example of Vermont’s modern architecture, and serves as a stunning combination of modernism and theology through place-based, material design.

Modern architect Victor Christ-Janer designed the Charterhouse in the mid-1960’s, adding to his already lengthy repertoire of commissioned religious buildings. (1) Christ-Janer’s churches, including the First Unitarian Universalist Church in Minnesota and the Cheshire United Methodist Church in Connecticut, exhibit a simplicity in utilitarianism, flat roofing, and sweeping interior communal spaces. Christ-Janer’s designs consistently showcased an impressive ability to translate religious ideals into modern aesthetics.

Christ-Janer worked as an architect, professor, and lecturer. He was also a practicing Lutheran, and occupied a unique position among his Harvard Five counterparts due to the dedicated integration of his religious ideals into his work. In the 1950’s and 60’s, Christ-Janer embarked on a lecture tour entitled “Aesthetics, Space and Theology,” in which he argued that modern design demonstrated security in the future because of its rejection of nostalgia. (2) According to Christ-Janer, this made modern design ideal for new religious buildings as a way to counteract the insecurity among religious institutions caused by the “God is Dead” movement in the US. It is clear, then, why Christ-Janer’s biggest architectural successes came in the form of religious designs, and why he was chosen to design the Charterhouse.