Philadelphia, PA, the host city of the 2022 Docomomo US National Symposium, “Yo! Modernism: The View from Philadelphia, is a World Heritage City whose history and architecture is most commonly associated with the founding of the United States. But this historic city also played an integral role in our nation’s adoption and adaptation of the Modern Movement.

The 1932 PSFS Building in Philadelphia is one of the nation’s earliest manifestations of Modernism in service of corporate America. The 1971-75 Penn Mutual Tower provides a dramatic demonstration of how the Philadelphia School’s brand of Modernism was utilized to make connections between corporate America and American history. The influence of the Modern Movement has continued to be felt in the 21st century with buildings such as 500 Walnut St, a new luxury high rise that is unapologetically contemporary yet referential to Modernism in its geometric articulation. The Penn Mutual Tower and 500 Walnut St are located within the same city block, mixed in amongst buildings from the 1830s, and all within view of Independence Hall (1732-53).

Buildings as Ad: The Penn Mutual Insurance Company Headquarters

Author

Daniel I. Vieyra, Ph.D., AIA

Affiliation

Docomomo US/Philadelphia

Tags

This density of historic architecture is typical throughout Philadelphia and is one of the primary attractions for attendees of this year’s National Symposium.

The following article takes a closer look at the Penn Mutual building and how corporations used architecture to convey a particular image or message to consumers and the world.

Buildings as Ad: The Penn Mutual Insurance Company Headquarters by Mitchell / Giurgola

By Daniel I. Vieyra, Ph.D., AIA

Buildings as Ad

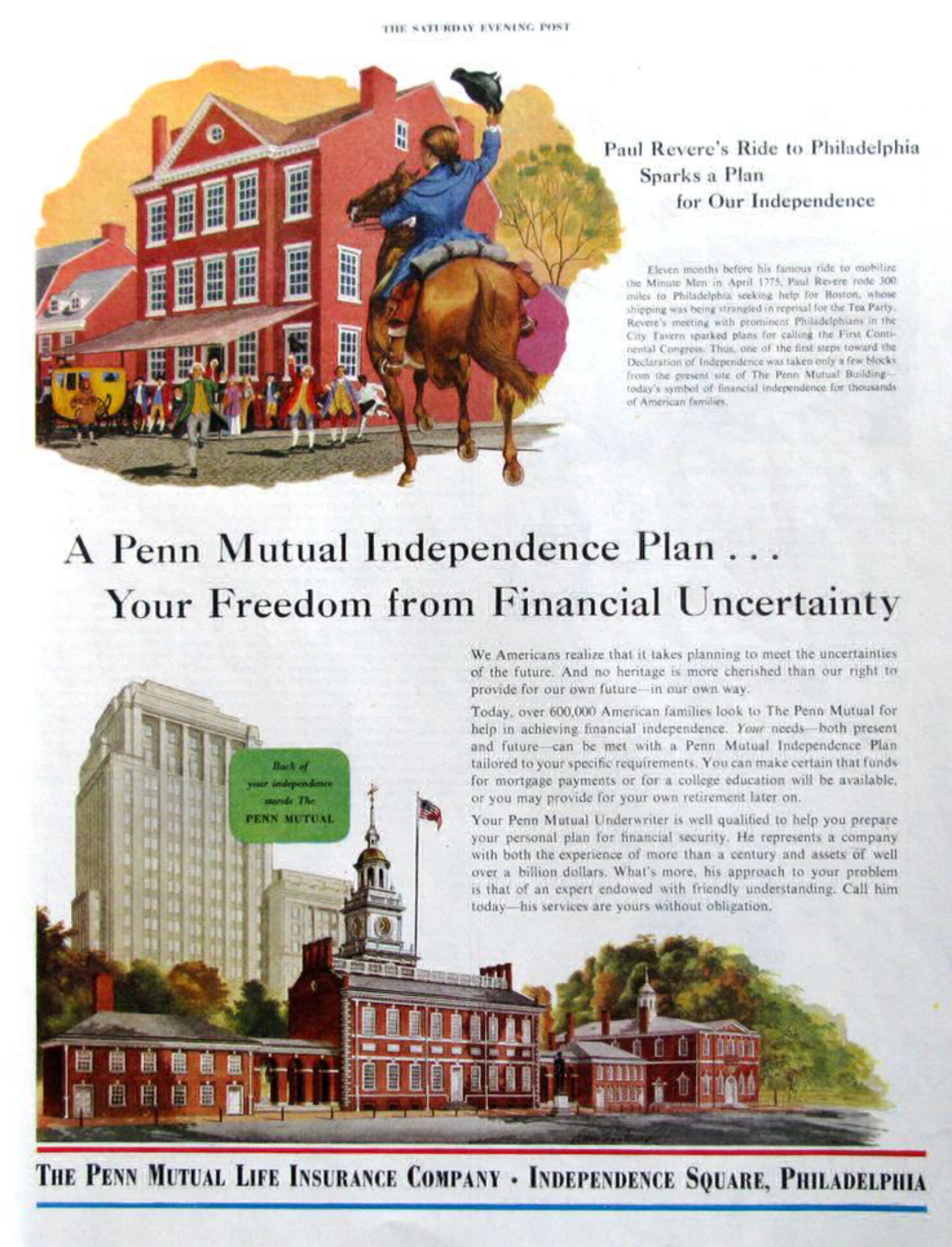

Throughout much of the 20th century the Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company was known by its moniker "Behind Your Independence ... Stands the Penn Mutual." Located just south of Independence Hall, the slogan reflected both corporate branding and the physical reality of its corporate headquarters as backdrop to Independence Hall.

Company Background + Building Evolution

Founded in 1847, the Penn Mutual headquarters initially were in Old City and Society Hill. Prior to the Civil War, the firm settled into a cast-iron structure at the southwest corner of Sixth and Walnut Streets. For well over a century, the company was to remain on this block, expanding its facilities with a series of buildings that reflected both the company’s growth and the changing times.

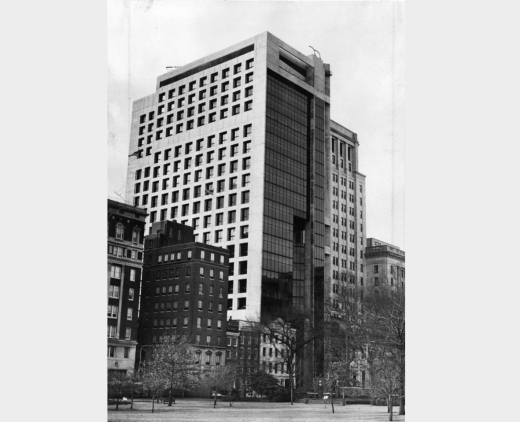

In 1913, the cast iron structure was replaced with a ten-story structure designed by Edgar Viguers Seeler, architect of the neighboring Curtis Building. Twenty years later, a tower designed by Ernest J. Matthewson was added to the east, created a gleaming, modern up-scaled restatement of the 1913 building.(1) Along Walnut Street, the old and new structures were united at their base by a Baroque inspired three-part projecting wing composition. From the north the ensemble created a twentieth-century backdrop to Independence Hall.

With the creation of Independence Mall in 1949, Independence Hall’s grand “front lawn” created an open space that afforded a vantage point that accentuated the asymmetry of the Penn Mutual ensemble. Penn Mutual’s buildings were viewed as a visual intrusion interfering with the colonial era icon; their future came into question.(2)

It is only with the coming of the Bicentennial and the addition of a third Penn Mutual building to the east, that the Penn Mutual ensemble was completed. Designed by Mitchell/Giurgola, this Late Modern addition created a balance, if not a symmetry, as a backdrop to Independence Hall, while reinvigorating Penn Mutual’s corporate image and its connection to one of the nation’s most venerated buildings.

Philadelphia as the Birthplace of Corporate Modernism

Corporate Modernism was not new to Philadelphia; in fact, Corporate Modernism arguably first came to the shores of the United States via Philadelphia. The 1932 Philadelphia Savings Fund Society (PSFS) building in Center City Philadelphia is generally recognized as a pioneer of Corporate Modernism.(3) Founded in 1816, PSFS, was the first savings bank to organize and do business in the United States. By the 1920s it was recognized for innovative outreach programs that encouraged children to open savings accounts and made financial services available to factory workers and immigrants. On the eve of the Depression, PSFS sought to tout its progressive approach to banking through its new building.

The resulting edifice, one of only two U.S. skyscrapers included in the 1932 Modern Architecture: International Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, is celebrated as a summation of European Modernism’s coming to America; at the same time, it is recognized as the style’s adaptation to corporate urban America. Combining William Lescaze's (1896-1969) experience with European modernism, and George Howe’s (1886-1955) Beaux-Arts background, with the desire of PSFS President James M. Wilcox for a forward-looking, tall building, the skyscraper substantially altered the pure European modernism that it embraced, appearing “in its extraordinary ambiguity, as reconciliation, synthesis, and prophecy."[8] Resting on a polished granite base, its T-shaped tower features ribbon windows and brick spandrels; the east and west elevations sport vertical piers that emphasize the building’s height while visually connecting the building to its famous rooftop red neon “PSFS” billboard. The composition foreshadows the large-scale adoption Modernism by U.S. corporations, and the subsequent Late Modernism that became part of the elusive “Philadelphia School.”

Giurgola and Penn Mutual

The Philadelphia School(5) was initially associated with the influence of Louis I. Kahn, whose bold monumental architecture went beyond Modernism, setting the stage for generations of Philadelphia architecture that followed. The architects of the Philadelphia School, who each had various associations with Kahn, took aspects of the movement and made it their own.(6) Among the first of the Philadelphia School to engage in Late Corporate Modernism was Romaldo Giurgola, who “fused his own very considerable and quite different design talent with Kahn’s geometric discipline and sense of solid tectonic form to produce a unique combination of order and virtuosity – Kahn's robustness and rectitude tempered with an Italian 'bella figure.’(7)

The twenty-two story glass and concrete Penn Mutual tower was the first high rise commission awarded the firm of Mitchell/Giurgola. In several ways, it demonstrates the firm’s ability to synthesize an “awareness of the thread of continuity in history with a confidence based on scholarship and respect for the deep structure of cities and places.”(8)

At the juncture of old and modern Philadelphia, with tall 1930s Penn Mutual buildings to the west and low nineteenth century buildings to the east, the new Penn Mutual building had to reconcile the two divergent street scales while preserving and respecting the company’s corporate history; as part of this challenge, the new building had to maintain and enhance its “dialogue” with Independence Hall.

Alternatively described as "... a contemporary fantasy of balconies, sharp diagonal fins, [and] plains cut back into the façade”(9) and “an assemblage of parts that evokes the multi-faceted reality of the city and weaves them into a lively fabric of a collage building,”(10) the façade facing Independence Mall alone consists of a clearly articulated elevator core, a historic building fragment, and an inflected glass office wall capped by attic level observation deck.

Dominating the western portion of this façade, the tower’s exterior elevator core, once capped by Penn Mutual’s logo, creates a strong vertical element, connecting the street level with a roof top observation deck. Continuing a Philadelphia tradition of linking the corporate and the civic, the deck provides an aerial view of the city including Independence Mall.

Set off by diagonals, a device often used by Giurgola to connect two points and break the grid while alluding to the diagonal slash of Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the concrete and glass elevator core serves to articulate the line between Penn Mutual’s buildings of the previous generation while also serving as a transition or pivot point.

Opposite the elevator, the façade is screened by a historic building fragment. Referred to as “a ruin” by Giurgola, the Egyptian Revival façade of the Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Company Building (1830) by John Haviland preserves a semblance of the historic scale of the street while creating an entry room.(13) The incorporation of this historic building element introduced “façadism” into the preservation lexicon; the Haviland building, in and of itself, represents a different era’s view of preservation; in 1902 the original three-bay structure was duplicated and doubled in size, and capped and unified by a corporate logo-bearing cornice by architect T.P. Chandler, Jr.

The fully glazed north facing façade reflects, in its layers and inflection, the foreground elements of the “ruin” and elevators while generously admitting light. The entire façade is capped by an attic level that exceeds the height of the Penn Mutual’s older building while articulating the observation deck and bearing the company graphic. At the same time, this attic treatment gives us an indication of the adjoining eastern façade.

The eastern façade consists of a beton brut inspired concrete framework. While providing environmentally sensitive sun shading, its vertically oriented module mediates between the scale of the building and that of its context. The façade treatment represents a refined version of its era’s Brutalism that simultaneously alludes to history and context. This façade’s grid shift to accommodate a Penn Mutual graphic along with its pronounced difference from its adjacent façade recalls aspects of the PSFS building.(14)

Finally, as one of Philadelphia’s prime examples of Late Corporate Modernism, this well integrated series of design responses that coalesce to create Penn Mutual Building raises a key question for future preservation efforts. In his review at the time of the building’s opening, Tom Hine lauded the building, "In its very celebration of complexity and ambiguity it eloquently summarizes the temper of its times.” At the same time, he feared that because, “It is not a symbol of only one thing,” but rather, “It is complex, and therefore unsettling . . . it probably would never work as a corporate trademark.”(15)

Given that the building is no longer occupied by the Penn Mutual Insurance Company, Tom Hine’s criticism might well have the antecedents of preserving Late Corporate Modernism in our time. Minus the corporate associations, the structure remains an exemplar of responsive design in its era; therein lies its preservation potential.

Notes

(1) Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Company, Philadelphiabuildings.org, accessed April 20, 2022.

(2) Kathleen Kurtz Cook, “The Creation of Independence National Historical Park and Independence Mall,” University of Pennsylvania, thesis, 1989.

(3) PSFS: Its Development and Its Significance in Modern Architecture, Author(s): William H. Jordy; Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 21, No. 2 (May, 1962), pp. 47-83, Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians

(4) PSFS: Beaux-Arts Theory and Rational Expressionism, Author(s): Robert A. M. Stern; Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 21, No. 2 (May, 1962), pp. 84-102, Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians.

(5) “Wanting to be the Philadelphia School,” by Jan Rowan in Progressive Architecture, April 1961, Vol. LXII, pp 130 ff

(6) It should be noted that the project architect for this project in the office of Mitchell Giurgola was John Q. Lawson. He studied architecture at Rice while it was under the leadership of William Caudill of CRS and did his graduate work at Princeton under the leadership of Jean Labatut, who is considered to be a seminal thinker, providing a link between modern and post-modern architecture. At Mitchell/Giurgola, Mr. Lawson was also project architect the Lang Music Center at Swarthmore College, and the Liberty Bell Pavilion that framed the view of both Independence Hall and the Penn Mutual Building beyond.

(7)“The Philadelphia Story,” Progressive Architecture, April,1976.

(8)Philadelphia School Exhibit: How Philadelphia Architects Formed a Movement Unified by Ideas, Reinvented Modernism, and Influenced the Entire World. A Philomathean Society Exhibit curated by Izzy Kornblatt and Jason Tang.

(9) Process: Architecture, No 2, October 1997, Thomas R. Vreeland, Jr. pg.258

(10) Process: Architecture, No 2, October 1997, Victor A. Lundy, pg.259

(11) Hine, Thomas. “Penn Mutual Building: View Changes the Face.” Philadelphia Inquirer 28 Feb. 1975: B2.

(12) Process: Architecture, No 2, October 1997, Ulrich Franzen. pg.259

(13) “Louis I. Kahn: The Making of a Room” Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania, February 6 through March 29, 2009.

(14) A Complicated Modernity: Philadelphia Architectural Design 1945-1980, Thematic Concept Statement, Preserve Philadelphia, Written by Malcolm Clendenin, PhD, Edited, with Introduction by Emily T. Cooperman, Ph.D.

(15) Hine, Thomas. “Penn Mutual Building: View Changes the Face.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 Feb. 1975: B2.

About the Author

Daniel I. Vieyra, Ph.D., AIA, is Professor Emeritus in the School of Architecture at Kent State University. He is author of Fill ‘er Up; An Architectural History of America’s Gas Stations. Having taught Architecture for over thirty years in Ohio, Daniel relocated to the Philadelphia area where he and his wife Katherine are currently involved in grand-parenting and preserving and somewhat irreverently updating a mid-century modern ranch/farmhouse outside Media, PA. Long interested in the everyday built environment and everyday Modernism, he organized the Society for Commercial Archeology 20th Anniversary Annual Conference, “Fins, Family, Fun and the Fabulous ‘50s” held in Wildwood, N.J. With Steven Izenour, he conducted the “Learning from Wildwood” studios and workshops sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania, Yale, and Kent State University. Daniel is past president of the Western Reserve Society of Architectural Historians and the American Institute of Architects Akron Chapter. He currently serves on the Board of the Society of Architectural Historians Philadelphia, where he coordinates the peripatetic The Elusive Philadelphia School; The Many Guises of Philadelphia Modernism series; he is also a Board member of Docomomo US/Philadelphia.