Plains Modern Part Two

Postwar Architecture in Kansas

In October of 2020, in the middle of the Covid-19 Pandemic, the Wichita Public Library, likely the first Brutalist building designed in the state of Kansas, became the state’s first Beton Brut building added to the National Register of Historic Places. The Library nomination was rushed through, along with a separate nomination for the adjacent Century II Performing Arts and Convention Center by concerned citizens against the wishes of developers and City officials. The urgency was created by proposals to tear down both buildings to make way for a replacement Convention Center and a separate Performing Arts Center. The Library already sat vacant and was the first building to be razed to make way for the new facilities. Despite Brutalism sometimes creating buildings that were difficult to love, the Wichita Public Library truly had its own constituency and was believed by many architects and architectural enthusiasts to be the best Modern building in Wichita, Kansas’s largest city.

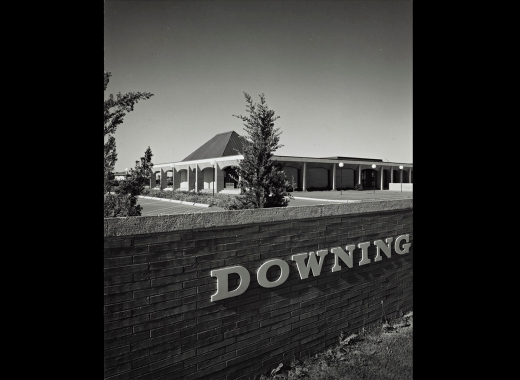

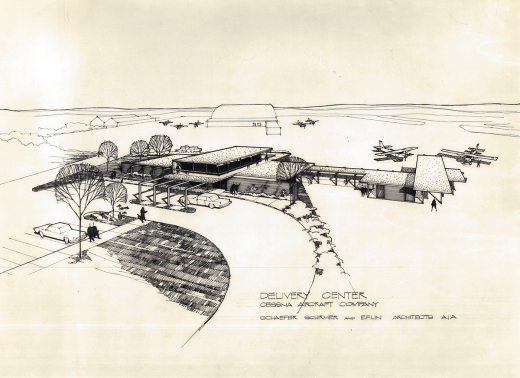

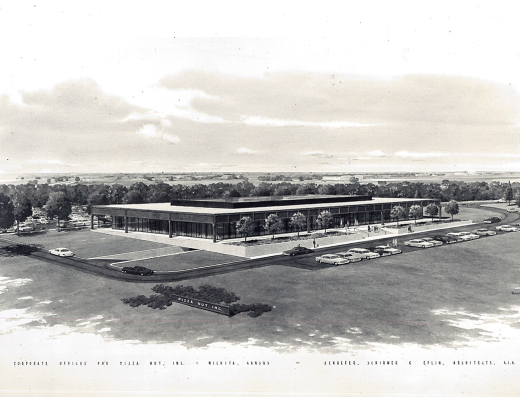

The Library’s design, which garnered an AIA National Merit Award, was created by the hands of skilled architects, Schaefer Schirmer & Eflin Architects. They were the most revered architecture firm in Kansas during the 1960s and 70s. Prolific and extremely skilled in designing Modernist architecture, they attracted the best talent to work in their offices. The Library became the breakthrough project for the young firm.

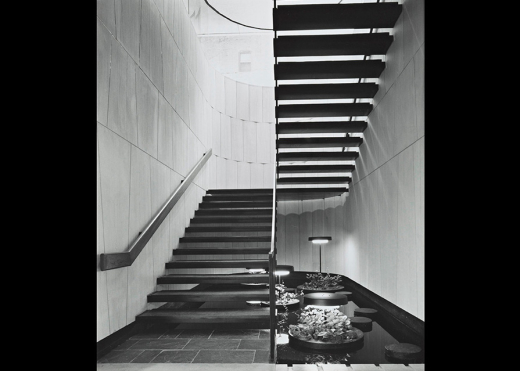

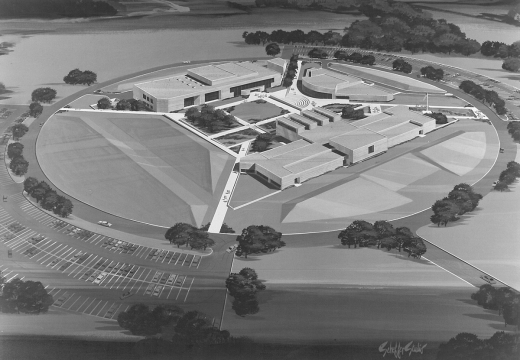

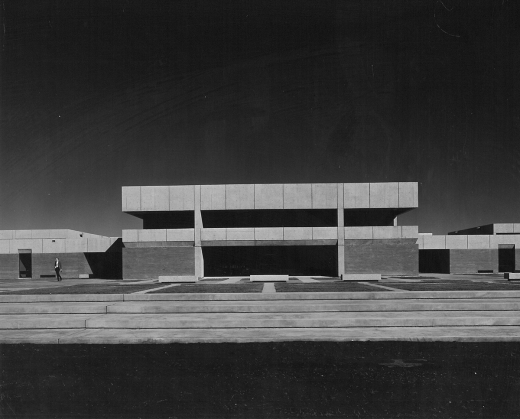

Meant to replace the 1915 Carnegie Library, still residing across Main Street, the new Public Library was designed in 1962-63, construction started in 1965 and the building was completed in 1967. The general shape is cruciform, including a single large rectangle with two smaller arms on the long, east and west elevations. It also features a full basement, main level, mezzanine, and upper level. The 90,000 square foot building is full of juxtapositions and contradictions: daylight & shadow, solid & void, heaviness & lightness, mass & space, vertical & horizontal, and concrete & glass. The monumental structure sits on a concrete podium elevated above the surrounding parking and streets. The library is very light-filled and airy for a Brutalist building. One enthusiast went so far as to call it “Brutalism Lite.”[1] The most significant feature of the library is its materiality, with the cast-in-place concrete structure both inside and out and the expansive areas of glass behind the concrete columns, defining the two great reading rooms to either side of the entry. The heavy “attic” or top floor seems to float over the reading rooms on legs of concrete. Even with the vacancy, the library remains in excellent condition and needs only minor repair and maintenance.

The firm of Schaefer Schirmer and Eflin felt so strongly about the quality of their finished project when it was completed that they hired Julius Shulman (1910-2009), famous California photographer of Modern architecture, to come to Wichita to shoot photographic images of the library.