Primary classification

Terms of protection

Author(s)

Location

125 Taneytown RoadCumberland Township (Gettysburg vicinity), PA, 17325

Country

US

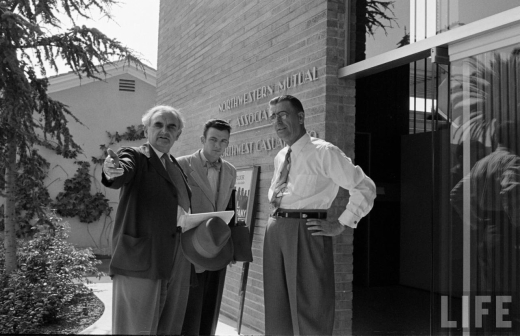

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Other designers

Architect(s): Neutra and Alexander (Richard J. Neutra and Robert E. Alexander)

Supervising architects: Dion Neutra and Thaddeus Longstreth

consulting engineer(s): Structural Engineers: Parker, Zehnder &. Associates

Mechanical Engineer: Boris Lemos

Electrical Engineers: Earl Holmberg and Associates

Building contractor(s): General Contractor: Orndorff Construction, Camp Hill/New Cumberland, Pennsylvania; Plumbing Contractor: Hirsch-Arkin-Pinehurst, Inc., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Electrical Contractor: Keystone Engineering Corporation; HVAC Contractor: Yorkaire Cooling and Heating