The challenge of historic preservation for a non-designated office building

The research and paper below by Vanessa Fernandez and Catherine Blain was presented at the 15th International Docomomo Conference in Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana, Slovenia this past August. Because the problems facing interior development and curtain walls of modern architecture in the United States are so similar, it is invaluable to have an example that takes a different approach.

Introduction

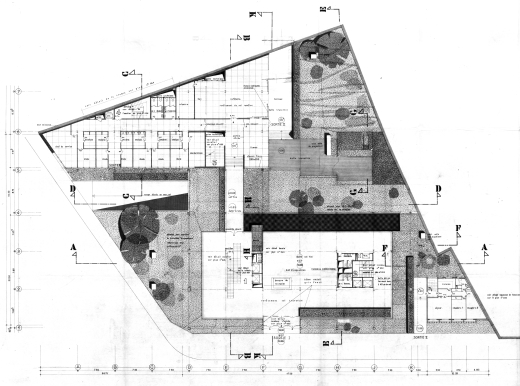

In the centre of Paris, very few modern buildings are as striking as the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme (MSH). Its architecture, combining metal and glass, gives it an exceptional status in the stone-built environment of historic Paris. Its location, at the corner of Boulevard Raspail and Rue Cherche-Midi, as well as its set back from the alignment, distinguish it distinctly from its nearby more bourgeois buildings. Looking beyond this exterior appearance, which leaves no one indifferent, the program and the history of the MSH make it also unique. Built between 1968 and 1970, it was originally designed to house research teams from different social science disciplines gathered around strategic geographic areas. The Ford Foundation supported the building construction with significant funding. One of the major actors of the MSH project, and who would be its first director, was Fernand Braudel (1902-1985). He was a renowned and charismatic historian, involved since the middle of the 1950s in the research and educational programs in the field of social sciences. And its main designer, Marcel Lods, was also a well-known architect at the time.

Since the interwar period, Marcel Lods (1891-1978) was recognized for the quality and the modernity of the projects he realised in association with Eugène Beaudouin (1898-1983), such as the Open Air School of Suresnes (1934) or the Maison du Peuple in Clichy (1935-1939). The latter in collaboration also with Jean Prouvé and Vladimir Bodiansky. After the war, Lods was appointed Architect of Public Buildings and was therefore entrusted with important government commissions, notably for the Ministry of Equipment and Housing and the Ministry of Education. These projects were often carried out in association with other architects.

In 1964, past the respectable age of 70 years, Lods created a new associative structure with two younger colleagues in order to develop his projects: Paul Depondt (1926-2007), who joined his office in 1957 after his architectural studies in America (IIT and Harvard), and Henri Beauclair (born in 1932), who was trained as architect and engineer in Switzerland. With them, Lods also created in 1964 a Research Group, called GEAI (Groupement pour l’Etude d’une Architecture Industrialisée) and aimed on the exploration of new systems of steel frame construction. The main projects of the time were the Science Faculty of Reims (1960-1969) and the social housing project of La Grand’Mare in Rouen (1962-1977). Developed from 1965, the project for the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme was designed in this same trio of architects, who brought into this metal structure building the very best of the international modern architecture spirit.

Although the MSH building was promptly recognized as a major realization of the 20th century, it was never included on the National historical monuments list. This lack of status became problematic when, in 2010, the building was first evacuated following an alarming assessment of asbestos presence and thus threatened by a necessarily renovation project.

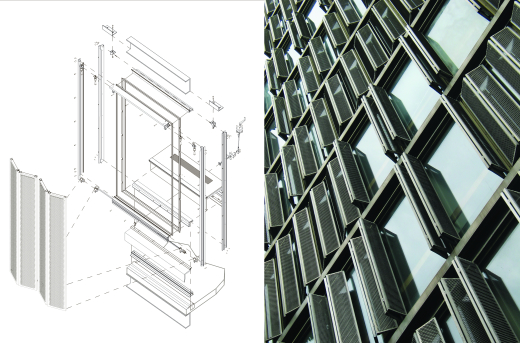

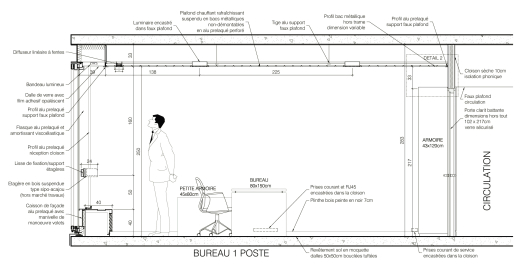

Despite the extensive demolition/reconstruction works and the extensive interior transformation which were brought by the renovation project, the building retained its exterior appearance. The renewed MSH also brought back its structure of research teams, what was not so directly obvious. This renovation, certainly one of the most interesting in recent years in Paris, was acclaimed by French conservation-restoration circles. Indeed, this project seems to have attained the objective of giving continuity through appropriate change, according to which it is expected that buildings of the 20th century should evolve.

The project was executed between 2013 and 2017 by the historic preservation architect François Chatillon (born in 1961), in association with Michel Rémon (b. 1949). The choice of this team was rather unexpected for a building that is still not protected by the Historical Monument designation. And this allowed for a unique project in the realm of office building renovation. But the public emotions stirred by the asbestos health danger and the fear that the building could be destroyed or transformed into a hotel, led the public agency in charge of University planning and building in the Ile-de-France region (EPAURIF) to commission an historic preservation team.

But this renovation raised many questions. In the end of these struggles and negotiations, were the researchers able to return to this building? How was the decision made to maintain the historic design of the facades, in a context of the need to meet increased thermal and energy performance requirements? How have architects preserved or reinterpreted the very special technical innovations of this building in terms of current comfort, construction and fire safety standards? How could the program have been developed with the restrictions imposed by the urban planning by-laws of the city of Paris? And finally, how did the renovation architects choose between contemporary evolution and respect for the historic building?