Modeled after roadside parks, safety rest areas (SRAs) were constructed as part of the Interstate Highway System to provide minimal comfort amenities for the traveling public. Early in their developmental history, however, design aesthetics moved in the tradition of roadside architecture that defined American highways in previous decades. Thus safety rest area sites emerged as unique and colorful expressions of regional flavor and modern architectural design. Safety rest areas functioned to create a context of place within the Interstate System, achieved through the implementation of unique and sometimes whimsical design elements and the use of regionally signifying characteristics. By the mid-1960s, SRA sites lined Interstate Highways, beckoning to travelers and offering respite from the hectic and potentially monotonous nature of high-speed Interstate travel.

Rest areas are to be provided on Interstate highways as a safety measure. Safety rest areas are off-road spaces with provisions for emergency stopping and resting by motorists for short periods. They have freeway type entrances and exit connections, parking areas, benches and tables and may have toilets and water supply where proper maintenance and supervision are assured. They may be designed for short-time picnic use in addition to parking of vehicles for short periods. They are not to be planned as local parks.

- A Policy on Safety Rest Areas for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, 1958

The limited-access of Interstate highways meant that a stop within these sites was often the only contact travelers had with regions they were passing through. Before the development of interchange business there were few stopping options available to drivers on newly constructed stretches of Interstate Highway. SRAs took the place of both the roadside park and the roadside store. While the sites did not allow for commercial business, they did provide a place where travelers could stop, rest, eat a picnic lunch, appreciate local landscapes and enjoy the use of comfort facilities. The functionality of these sites made feasible the less tangible directive of connecting people with the regions they passed through by replacing the local flavor that would have once been readily accessible from the roadway.

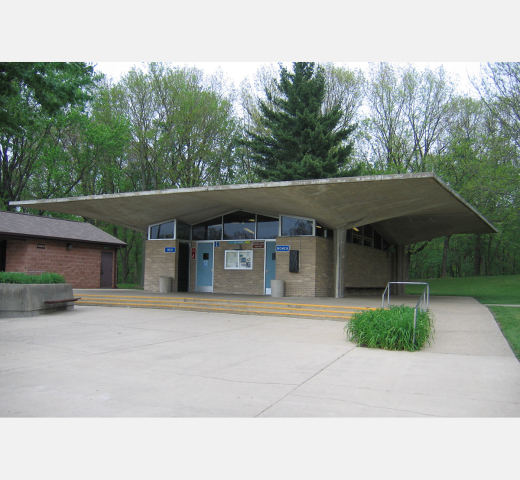

Architecture was an essential element in developing the context of a site. Safety rest areas were designed around a central architectural theme which was established in the toilet building and then reflected in the other structures, most commonly picnic and information shelters. SRA structures, and the sites as a whole, were to be both functionally and aesthetically satisfying, creating environments that were at once relaxing and engaging.

When the American Association for State Highway Officials (AASHO) defined safety rest areas in 1958, their spare characterization did not foreshadow the many wonderful and diverse sites that would be constructed during the following decades. A Policy on Safety Rest Areas for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, quoted above, standardized the basic elements of SRAs while discouraging creative embellishment in the interest of cost effective construction. Despite the lack of creative suggestion on the part of the Federal government, state officials who were charged with the task of designing and constructing safety rest area sites saw their task as one equal in importance to Interstate road building itself. In 1957, George T. O’Malley, of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources speaking at the 16th Annual Ohio Short Course on Roadside Development, iterated this point. “In view,” he stated, “of the huge sums of money spent on development of new super highways, should sanitary facilities be restricted to a privy type toilet and hand pump water supply? Should not the rustic design be replaced by the modern in keeping with the highways being served?”

Safety rest areas were legislated as part of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, the legislation that created and funded the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, and were to be constructed on the same Federal-state shared funding basis as the highway system itself. The 1958 policy guidelines recommended that sites be constructed concurrently with road construction, minimizing the cost and effort of installing entrance and exit ramps and parking areas. As a result, the construction of safety rest areas in most states can be linked to the completion of highway segments.

The concept of safety rest areas was drawn from existing roadside parks, facilities that American drivers had come to expect and appreciate in the decades preceding Interstate construction. Initially sited by drivers stopping to fulfill necessity or pleasure, roadside parks were eventually constructed by state highway departments which recognized that people would stop along the nation’s highways. Establishing particular points for stopping reduced the number of automobiles parked at random and provided locations that drivers could stop at a safe and comfortable distance from traffic. By the mid-1950s, most states had well established roadside development programs that constructed and maintained an intricate system of roadside parks. Such sites were used to showcase the beauty of their respective states while fulfilling the primary needs of travelers to pull off the road for rest, sightseeing or picnic facilities. Most roadside parks did not have toilet facilities and few had running water. Expectations on the part of travelers to encounter these sites frequently, coupled with the limited access of Interstate road design, made inclusion of safety rest areas within the Interstate right-of-way a necessity. Limited access made it more responsibility than prerogative for state governments to provide drivers with locations to safely leave Interstate roadways at regular intervals. As indicated by the 1958 Policy Guidelines, “In the interest of safety and convenience to the motoring public, safety rest areas are necessary.”

As the Interstates began to restructure American life, American expectations began to influence how the Interstates, or more specifically, how Interstate amenities took form. The generation of Americans who had come of age during the interwar years had responded to the visual language that was established by roadside business of that period. Exaggerated and fantastical building forms along with quaint cottages and colonial facades defined the experience of the American roadside. The modern aesthetic that emerged dominant in the postwar era informed Interstate construction. Safety rest areas would become a marriage of formal ideology and visual sentimentality, responding to the idealism of past and present. The architectural design of SRAs would be the manifestation of this marriage, taking on the characteristics that had defined regional and exaggerated elements of roadside commercialism while forming a new modern vocabulary.