The following is excerpted from a talk prepared for the Universita degli Studi di Sassari, Sardinia in October, 2015. All images are by author unless otherwise noted.

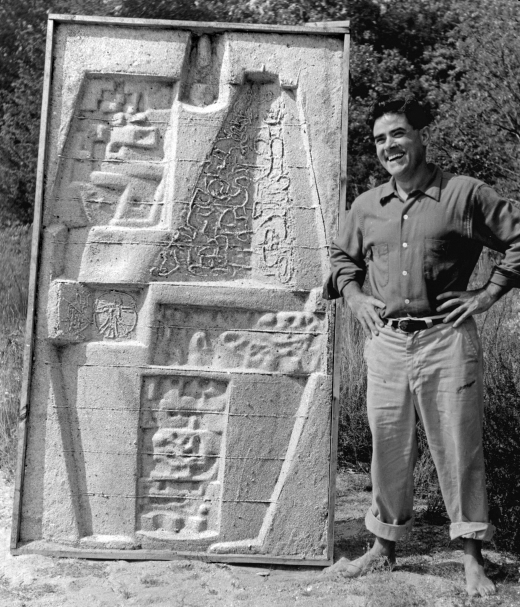

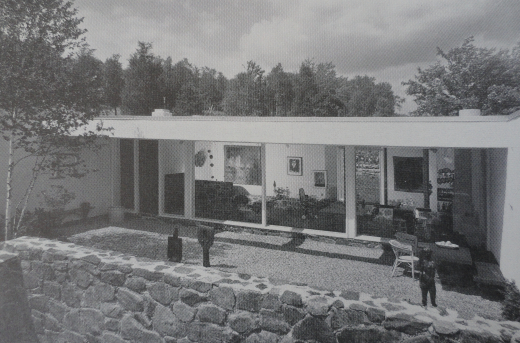

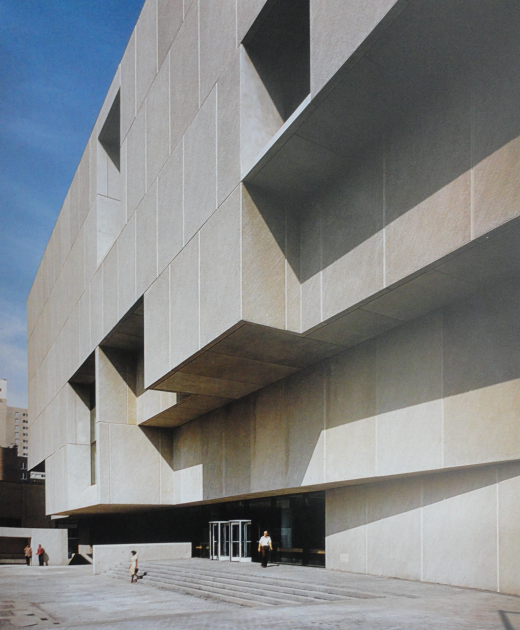

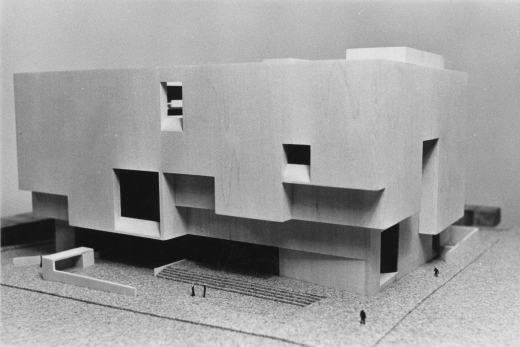

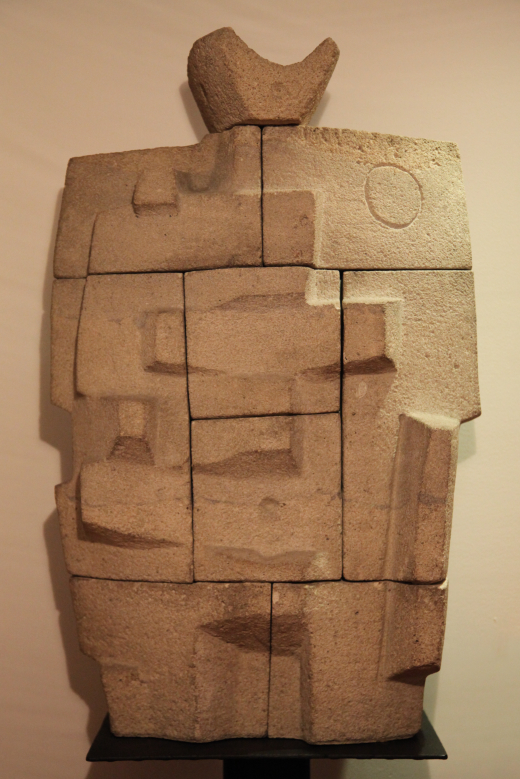

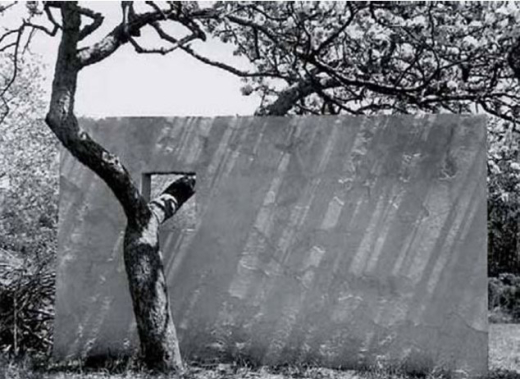

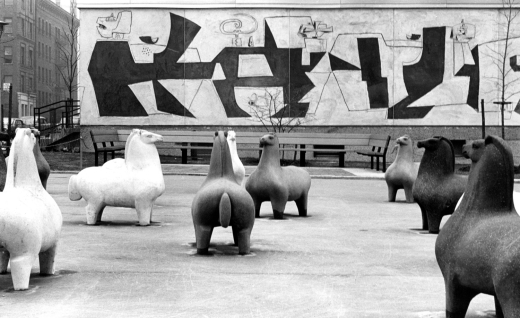

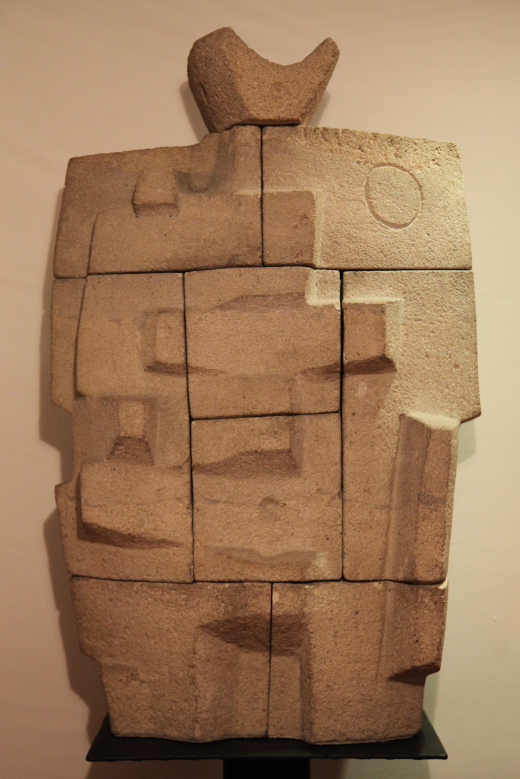

From the mid-1930’s through the 1980’s, New York City and its immediate surroundings were a nexus for the Modern art and architecture movement that had relocated from Europe to escape the rise of fascism and the destruction of the Second World War. The community included immigrants who had been active in the formative years in Europe and native-born Americans, generally a half-generation younger than their colleagues. Key among the transplanted Europeans were Marcel Breuer and Costantino (Tino) Nivola. I have good fortune to have known both men from my early childhood onward and, on entering the world of architecture, to have worked for and with each of them. My father, Richard Stein, collaborated with Tino on numerous projects beginning in the early 1950’s and I spent significant time with the Nivola family during this period.