This article was originally published in Wisconsin People & Ideas magazine, Summer 2022, and has been reprinted here with permission.

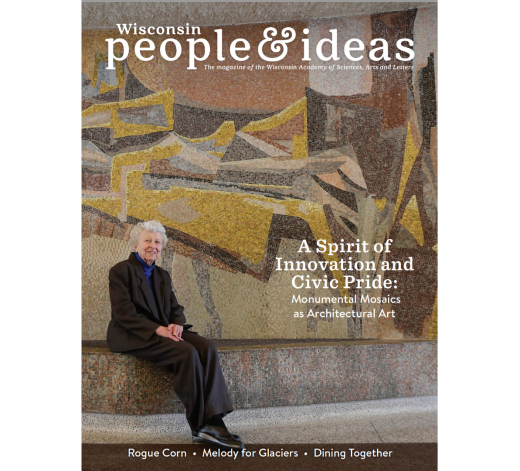

Milwaukee's Monumental Modernist Mosaics

Author

Lillian Sizemore and Eric Vogel

Tags

I’ve accepted the idea that art and architecture are one and the same…anything you call separately as art, whether it be sculpture, or painting, or mosaic, or any other form of expression, it must be an integrated part of the whole. Therefore, it must begin to show up in the Architect’s thinking.Karel Yasko, Wisconsin State Architect, 1960-1963

How did Milwaukee, in the middle of the country, in the middle of the 20th-century, come to have some of the nation’s most inspiring and monumental mosaic murals? How is it that many churches, libraries, schools, government buildings and public spaces across Wisconsin have mural-sized mosaics fully integrated into the architectural surroundings?

Monumental mosaics are a critical part of architecture, and they convey an important public message on the role of art in expressing shared values. A close look at four mosaics commissioned in Milwaukee at a time when modern art and architecture were capturing a new spirit of innovation and civic pride, reveals different approaches to using mosaic as an architectural art form and presents a unique perspective on the history of arts in Wisconsin.

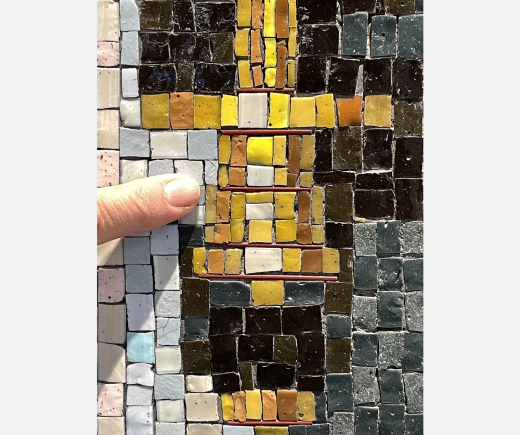

In historic preservation terms, a monumental mosaic is both large enough and striking enough to be considered a "character defining feature" of the building. Mosaics have traditionally been made by hand-setting small pieces of stone, ceramic, or glass (known as tesserae) in a decorative pattern onto a mortar base. Among the many techniques of working mosaic are Opus musivum (associated with the glass mosaic for walls) and lithostrotum (mosaic used for floors).

For thousands of years, mosaics have played a critical role in cultural storytelling by illustrating religious, political, and mythological traditions throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. At the turn of the 20th-century in the United States, a large Italian immigrant population arrived from Europe, which included skilled craftsmen and artist entrepreneurs. The mosaic and terrazzo workers from Northern Italy were regarded as ‘the aristocracy of the Italian work force’ because their work was so highly specialized. The aesthetic value of the works done by these craftsmen satisfied the American desire for architectural embellishment using mosaics, from Beaux Arts projects at the turn of the century through the Art Deco period of the 1920s.

During the Depression, between 1930 to 1942, the Works Progress Administration hired American artists, who were often trained by Italian craftsmen, to execute hundreds of murals, in both fresco and mosaic around the country. Many American soldiers who fought in the European theater and artists who traveled to Italy after the war became enchanted with traditional Italian art forms. The post-war American mindset was infused with romantic notions of Italy that percolated into public consciousness through television, film, music, food, and fashion. As trade restrictions eased between Italy and the U.S., commercial activity took a significant step forward with the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway which connected trade routes in the Great Lakes region to Europe and other parts of the world. For Milwaukee, the new seaway brought crates of mosaic fabricated in Italy directly into the city’s port.

Another significant initiative occurred in 1962 when President John F. Kennedy signed a directive titled “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture.” The three-point policy laid out a vision for the finest architectural thought, the elimination of an ‘official style’ with encouragement of professional creative competitions, and the integration of landscape into site-specific development. Karel Yasko, former Wisconsin State Architect, was responsible for commissioning both emerging and established artists on behalf of the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) through the Commission of Fine Arts. The GSA directed the largest building program in the Federal government, one which assigned a half-percent of any construction budget over $200,000 to be reserved for fine arts. Murals, sculpture, stained glass, and fountains were commissioned by architects as character-defining features of new public buildings receiving federal funding. Commercial builders followed suit. Soon shopping malls, grocery stores, banks, libraries, universities, as well as Federal buildings and many other public and civic buildings, integrated public artworks that were considered as essential to the construction as plumbing or air conditioning. Mid-century artists and architects reintroduced mosaic art, known for its visual effectiveness at monumental scales, as a striking new feature of the American built environment.

Allen-Bradley Company Headquarters

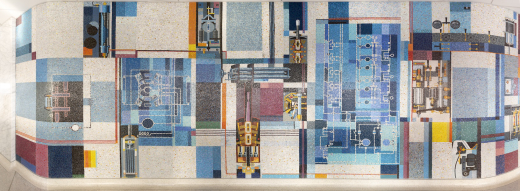

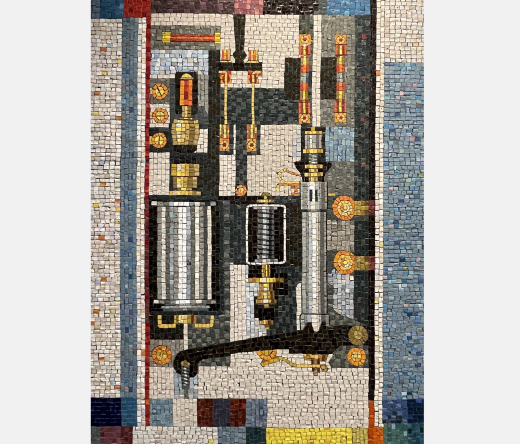

American industrial prowess emerged as an important public theme in the post-war years and businesses like the AllenBradley Company in Milwaukee had important stories to tell. In 1955, Harry Bradley, one of the founding family members of the Allen-Bradley Company (now Rockwell Automation), along with architect Fitzhugh Scott, and Vice-President Robert Whitmore, wanted to create a mural in celebration of the company’s long history of engineering innovation.

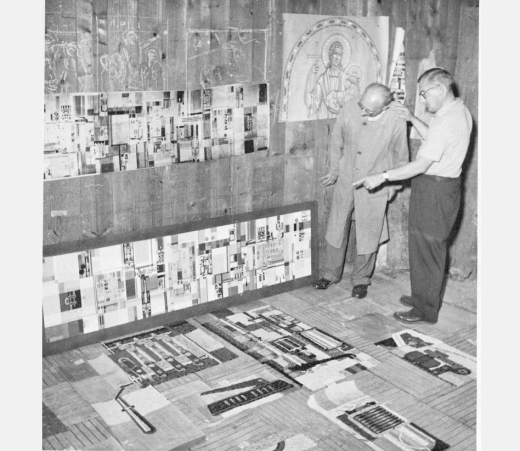

The artist they chose, Edmund Lewandowski, was born in Milwaukee in 1914 and had his first exposure to the awe-inspiring, mosaic-filled cathedrals of Europe when he served in the U.S. Air Force during World War II. This first-hand encounter with the beauty of mosaic, along with later visits to the Murano glass foundries near Venice, stimulated his imagination toward new possibilities with the medium. When selected by Allen-Bradley, Lewandowski was already a well-known Precisionist painter and mosaicist and president of the Layton School of Art and Design in Milwaukee, and his mural was intended to be a monumental undertaking from the start. Lewandowski spent a year studying the company, its patent drawings, products, and historic artifacts. Collaborating with technical advisors from Allen-Bradley, he developed an impressive plan for a forty-foot-long mosaic mural in the company’s cafeteria, where workers and managers could connect their daily labors with the story of the company’s achievements. In a colorful floor-to-ceiling display, a timeline from 1893 to 1952 depicts twenty-six devices and components unique to the company’s history of invention and product development. Three large blueprints of electrical diagrams anchor the mural’s composition and link the chronological survey to the company’s long-term commitment to research and development.

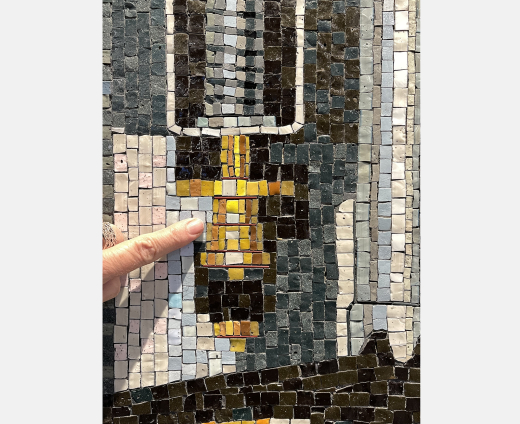

Besides relying on compositional methods and graphic techniques that he had employed over the years in his Precisionist paintings, Lewandowski worked closely with the renowned mosaic studio of Giulio Padoan in Venice to combine his many studies into one cohesive schematic composition. Lewandowski and the mosaicists executed the mural using Byzantine-style materials, employing traditional smalti, a thick glass material specifically formulated for mosaic, set in a tightly spaced, brick-like arrangement. The engineering inventions are depicted with astounding realism and detail, using graded colors to suggest volume in three-dimensions; handles, screws, levers, coils, wheels, and wires seem to advance from the surface thanks to the mosaicists’ technique of using contorni tesserae—long, thin pieces of glass (think linguine) used for outlining the object to set it apart from the background. Electrical symbols and linear graphics take on the appearance of an ancient symbolic language. Upon close inspection, we see that the color blocks are flecked with a juxtaposition of both warm and cool colors, an ancient mosaic technique used to add visual vitality.

The Allen-Bradley Company mural—completed and installed in 1956—as well as the other mosaic murals discussed here, were produced using the indirect method, a pre-fabrication technique established in the late-1800s as a cost-effective solution for large mosaic works. The artisans glue the tesserae face down on paper sections marked with the design outline in reverse image. Installers position the sections on the mortar base of a prepared wall, taking care to avoid visible seams. The paper backing which faces outward is then dampened and peeled away, with a final wash and buff to reveal the sparkling surface. With abundant daylight flooding into the cafeteria from long ribbon windows on the opposite wall, the mural is “radiantly reflective, vibrant in color, majestic and beautiful.” Lewandowski described the mosaic as “a graphic, symbolic portrait of the Allen-Bradley Company,” depicting the power of human invention and the joy of communal achievement.

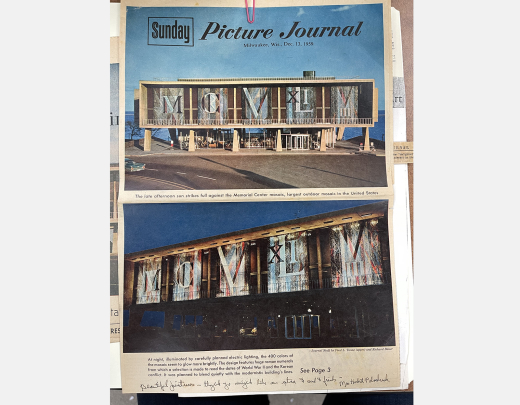

Milwaukee County War Memorial Center

Despite the post-war economic boom enjoyed by businesses like Allen-Bradley, America was still recovering from the human losses endured during World War II. Cities around the country were encouraged to build memorials to their fallen soldiers, and in 1944, three women’s service clubs joined forces to organize for a distinctive victory memorial to commemorate Milwaukee’s participation in the World War. Drawings and proposals were made for a new Milwaukee County War Memorial Center over a period of years, and construction began in 1955. By this time, Eero Saarinen had taken over as design architect after the death of his father and business partner, Eliel Saarinen, with Maynard Meyer serving as associate architect in Milwaukee. The younger Saarinen brought an innovative solution to the problem of how to convey a sense of monumentality and solemnity with a relatively small building situated on a large lakefront site. He positioned the memorial building on the very edge of the bluff facing in all four cardinal directions with a commanding mosaic planned for the west façade looking back towards the city. The bold cantilevers of the modernist structure create a floating cruciform shape made of cast concrete, steel, and glass that seems to hover above, yet be a part of the landscape. The requirements of the building brief presented a challenge given the limited budget, the large number of stakeholders, and the many outside opinions. The building had to be designed to accommodate an art center, memorial offices, and large event spaces, while remaining an elegant and meaningful monument.

To achieve this, Eero Saarinen decided to create a series of contemporary mosaics covering the entire west façade that would set a somber and dignified tone for the entire building. He selected Edmund Lewandowski for his proven “instinct for monumentality,” which Saarinen considered “outstanding in the country.” Chosen over well-known European artists Fernand Léger and Joan Miró, and considered more experienced with mosaic than the American artist Stuart Davis, Lewandowski was asked by Saarinen to create five panels measuring 25 feet tall x 16 feet wide to be positioned between the tall windows of the interior event space. As the symbolic gateway to Lincoln Memorial Drive and the lakefront, they are designed to be visually effective from a great distance and are especially magnificent when viewed at night. Stately Roman numerals are aligned in sequential order to commemorate the start and end dates for both World War II and the Korean Conflict. Reading from left to right the mosaic depicts: MCMXLI (1941), MCMXLV (1945), MCML (1950), and MCMLIII (1953). But the sequence is not a literal transcription of the dates. In a shift away from the realistic imagery used in his earlier mural at Allen-Bradley, Lewandowski created a more abstract composition for the War Memorial. The Roman numerals designed at various sizes lend a sense of deep perspective. Like searchlights, prismatic lines run diagonally through a nocturnal field of dark blue-violet. The organic placement of tesserae rises in waves from the bottom of the panels offering an aquatic weightlessness. The numerals float in a dreamlike background, submerged by time and veiled by memory. With their memorial purpose, one senses the impact and pain of the wars and the actual toll of lives lost.

Lewandowski and mosaic craftsmen in New York understood each other’s languages. The mosaicist is an artist but also a scientist who understands the intricacies of visual perception, applying both color and light theories. Lewandowski the painter understood that surprising combinations of color, when juxtaposed and seen from a distance, are perceived as one dynamic synthesis. Together, they pioneered a visually powerful work that stands as one of the earliest examples of modern mosaic. The mural employs an ancient yet innovative method that was just re-emerging at mid-century and had not been used for millennia. With its roots informed by the ancient pavement technique known as opus scutulatum, this work is characterized by irregular pieces of colored stone interspersed with a regular cut background. In the panels, we see a mix of stone and glass in both large and small cuts, interspersed with substantial chunks cut from formed glass disks or pizze. This technique enhances the layered effects of Lewandowski’s painted cartoon, interweaving sky, lake, and architecture through bold color and texture. The sequence of chromatic murals enlivens the Brutalist concrete structure of the memorial to evoke deeply emotive themes of time, memory, and loss, in a monumental achievement that transcends the mundane.

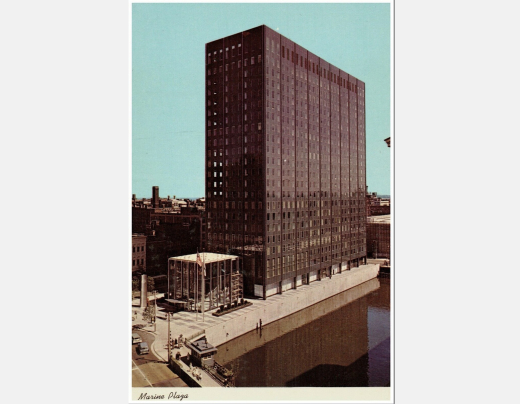

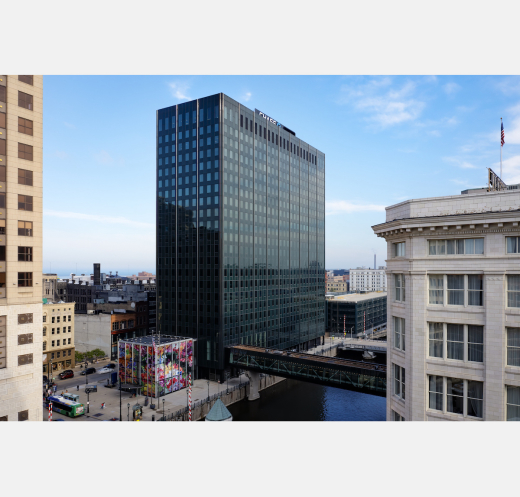

Marine National Exchange Bank and Plaza

In the mid-twentieth century, it was common for banks to commission grand mosaic installations in their buildings. Following the work by the Millard Sheets Studio for Howard Ahmanson’s Home Savings of America in California, artist-patron collaborations in commercial buildings demonstrated how decorative mosaics could embellish the glass and steel of American architectural modernism. The Bank of Italy, founded in San Francisco in 1904 to serve working-class Italian immigrants and which later became Bank of America, commissioned many monumental mosaics and emblems into their branches. As we see in the fine example for the Marine National Exchange Bank and Plaza, Milwaukee was not to be outdone by other cities. The Marine Bank mosaic by Merritt Yearsley (1920-2010) reveals a merger between the artist and his medium. Yearsley studied at Milwaukee’s Layton School of Art and in Pietrasanta and Ravenna, Italy, where many of the mosaics he had admired during the war had been created. He was an accomplished welder and often used copper and piping in his sculptures.

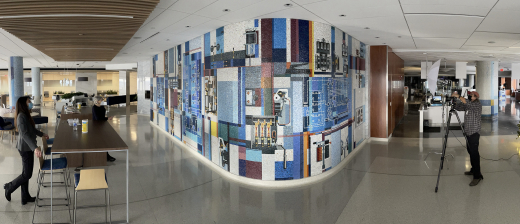

The Marine National Exchange Bank (now known as Chase Tower) was constructed to great fanfare in 1961-62, combining a twenty-two-story office tower with green glass curtain walls in the new International Style, and a three-story clear glass cube, serving as the entry pavilion. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel wrote in its “Modern Milwaukee” section published March 25, 1962: “The clean lines and spacious appearance given to the block bring a fresh breeze into a section surrounded by some of the oldest buildings in the city.” The building, the second-tallest in downtown Milwaukee at the time, commanded the skyline. The architects, Wallace Harrison and Max Abramovitz from New York, were already known for their innovative use of glass at the Corning Museum of Glass, built in 1951.

Upon entering the glass cube, visitors are presented with narrow, twin escalators—one going up, the other coming down. Ascending to the second floor, we are greeted by a dramatic 50-foot-wide mosaic mural running the entire length of the room as a backdrop to the teller booths situated below. The mosaic is flanked to the east and west by white Carrara marble walls whose book-match patterns mirror each other, and by double height windows with long, semi-transparent drapes that add to the vertical drama and theatricality of the space.

According to Yearlsey, the mural tells the story of the new St. Lawrence Seaway, inaugurated in 1959 just two years before the Marine Bank building was completed. The mosaic commemorates the bank’s historic interest in transcontinental railways and Great Lakes shipping. The mosaic is cartographic, a symbolic depiction of American natural resources. Yearsley cleverly employs an array of mixed media in the mural to portray Western mining, Prairie wheat, and Midwestern lakes using modern shapes and distinctive textures set against a warm marble background.

In his mosaic for the Marine Bank, Yearsley incorporated unique personal innovations, blending his trade skills in sheet metal and welding with his craftsmanship as a stone mosaicist. The unprecedented and surprising inclusion of metal sculptural pieces, set inches above the surface of the stone, further embellishes the awesome drama of this monumental abstract design. Waves of cut and braised copper or brass are positioned alongside thin, metal strips textured with what appear to be highly-controlled linear bubble welds. The metal portions now bear the verdigris patina of age and are even more beautiful for it. Mr. Yearsley’s son, Greg, describes this detail: “I especially like the nubbly mini-popcorn-like pieces that add so much texture, color, dimension, and visual interest and contrast so remarkably with the stone. That seems like a creative and unique touch to me. And it is done in just the right amount to be significant and noticeable, but not to be too overblown or distracting.”

Yearsley’s masterful handling of his material conveys much of the narrative intent. The careful selection of stone and marbles are laid with attention to the different grain patterns which amplify the vitality of the surface. The long lines that crisscross dramatically through the composition are made with thick, raised cubes of pure black marble, interrupted with dashes of wavy ondulata gold smalti. In a composition that is primarily abstract, elongated geometric shapes portray abstracted wheat fields of the Prairie region, but at far right, a distinct golden outline clearly depicts the five Great Lakes, with a range of watery blue and teal shapes hovering underneath. The large ochre tesserae used for the background, when seen from a distance, provide a grounded solidity in counterpoint to the reflective quality and scale change of the smaller cuts in the glass areas. In mosaics, a background does not simply serve to “fill in,” but is always carefully considered to accentuate the foreground elements.

In 2008, a Chase Bank manager wrote to the Yearsley family: “We receive many comments every day. Most people comment on the detail and the obvious length of time it must have taken to be completed. The most common question we hear is, what’s the meaning…?” Yearsley’s monumental mosaic remains enigmatic. Like a theatre backdrop, it sets the stage for the bank’s commercial activity, but it is not grounded in a specific time period or storyline. Without reference to modern day figures or industry, the mosaic map could effectively suggest ancient trading routes active hundreds of years ago. Yearsley’s abstract composition has an enduring quality that rises above the day-to-day commercial activity to present a unique contribution to Milwaukee’s modernist survey.

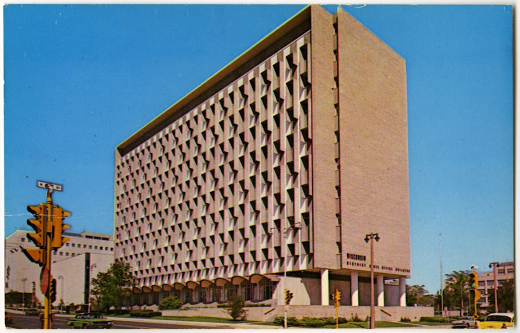

Wisconsin State Office Building

An impressive suite of ten mosaic murals by artist and University of Wisconsin (UW) professor, Marjorie Kreilick, who was born in 1925, resides inside Milwaukee’s State Office Building. Located on Wells Street, adjacent to the Milwaukee Public Museum and just down the street from the Milwaukee County Courthouse, the State Office Building houses the Milwaukee office of the Governor and several other state departments and social service agencies. The building was designed by the firm of Grellinger & Rose Associates and overseen by Karel Yasko, a Yale-trained architect with an undergraduate degree in fine arts, who was Wisconsin’s state architect at the time.

In 1961, Yasko selected Kreilick to meet with the team of architects and contractors for an initial planning meeting. Kreilick remembers the men sitting around the table expounding upon their ideas, suggesting themes about the state’s agriculture and industry with montages of dairy cows, breweries, cheese, and wood pulp for the ten large scale mosaics, apparently without considering that the invited artist might have her own ideas for the project. When the conversation came around to Kreilick, she stood up and said, “I’m sorry, gentleman, I’m not interested in that.”

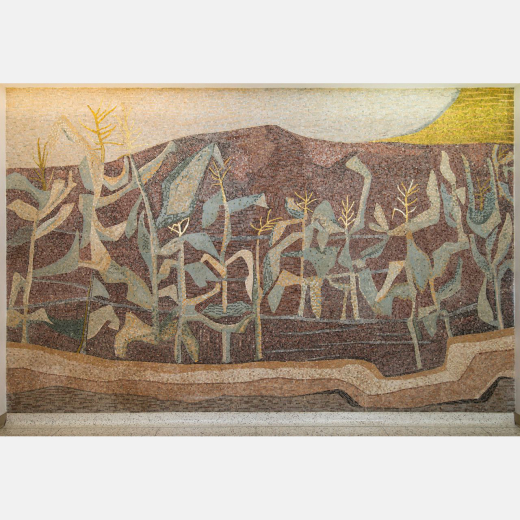

Kreilick’s proposal separated the state’s geography into nine ecological divisions as the subject matter for the murals, and she was willing to walk away from the commission in order to stay true to her vision. As she observed, “Industries come and go…I wanted to show the state before man got here, to show the ecological areas and recognize some of the contributions that came from the indigenous Indians, the landscape before white man came. I wanted to do something that would be the essence of Wisconsin.” At Yasko’s suggestion, a second meeting took place in which the team unanimously accepted Kreilick’s proposal.

In a field dominated by men, it was not the first time Marjorie Kreilick had to step into her agency as a confident artist with something to say. She was only 35 years old when she received the commission for the State Office Building. Shortly after the first meeting, she set sail for Rome on a Prix de Rome Fellowship, where she would work side-by-side with her trusted Italian mosaicists. Kreilick controlled crucial decisions about the color palettes for each mural for which she had made scaled, preparatory cartoons. She visited quarries in Carrara to hand-pick slabs of marble to be used in the fabrication process. She worked at the Monticelli Studio in the mornings, art directing and cutting stone alongside the craftspeople, and returned to her Rome Academy studio to work on her painting, sculpture, and printmaking in the afternoon and evenings.

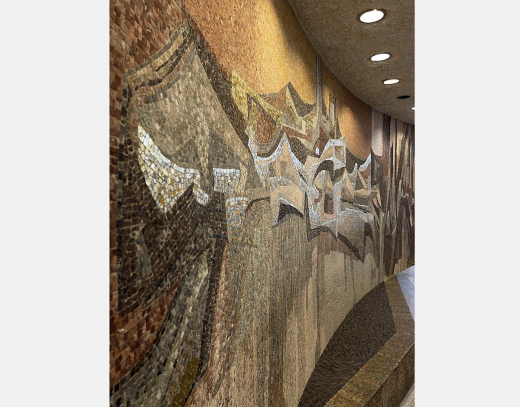

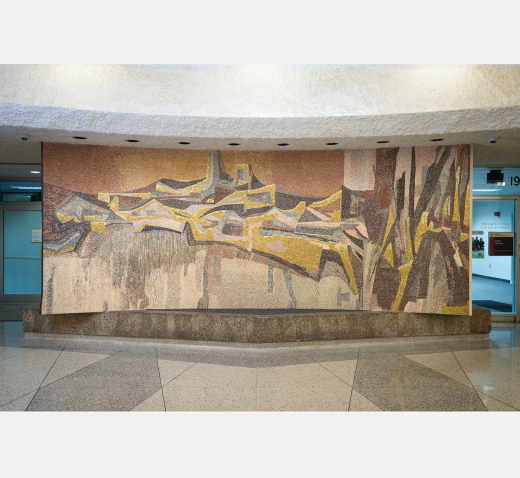

At the State Office Building, the suite of interior mosaics is positioned in the elevator lobby of each floor and along one large, curved wall in the main entry lobby. The ten-story rectangular block of concrete and Cream City brick has a side entry pavilion with glass walls and arched concrete awnings over three pairs of glass and metal doors. The curved first floor awnings span the length of the southern facade, with a rhythmic grid of upper floor windows accented by protruding sunshades, or brise soleils. These not only create changing patterns of light and shadow over the course of the day but also keep excessive light and heat from the interior.

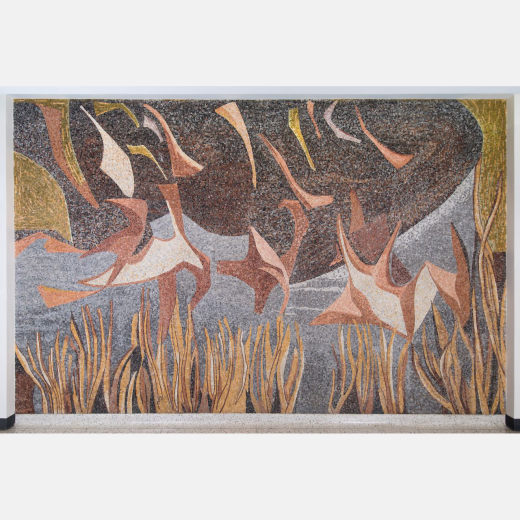

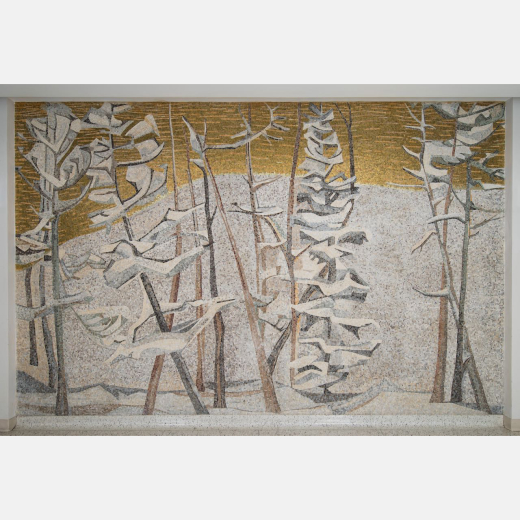

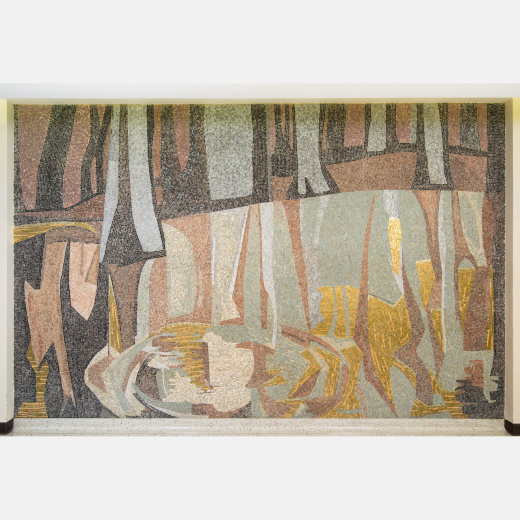

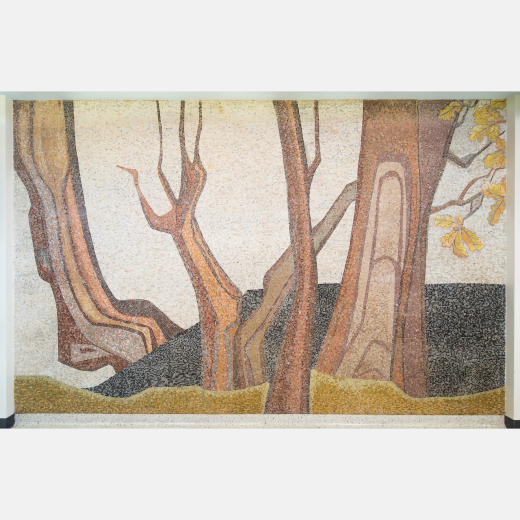

This careful attention to the use of natural daylight was a key consideration for the monumental mosaics inside. Because of the oblique angle of the natural light illuminating each mosaic, the colors and forms of the landscapes seem to shift as the viewer passes by. Each mural measures approximately 15 feet wide x 10 feet tall, and taken together, present nine different landscapes from across the state: the Cultivated Fields of Maize; the River Groves; the Burning Prairies; the Coniferous Forests; the Meadows; the Swamps; the Lakesides; the Deciduous Forests; and the Cranberry Bogs—along with a tenth mural dedicated to Wisconsin's state motto, ‘Forward.’

Kreilick designed each of the State Office Building murals to human scale, encouraging interaction directly with the landscapes. There is a physical immediacy and accessibility different from the Lewandowski and Yearsley works, that are positioned overhead and are meant to be seen from a distance. Kreilick extends each composition to align with the floor and offers the viewer a path into each scene through carefully placed foreground elements—a burst of sunlight reflecting on the water, or an opening in the tree line. Passing through the lobbies during a busy workday, one senses the deep well-being and inspiration that comes from contact with nature. Kreilick purposefully designed the murals with this in mind, well before researchers coined the term ‘Nature Deficit Disorder.’

The strong directional movement of the mural Forward in the lobby conveys the concept of pressing onward, a rhythmic advance. The broad concave surface, with its abundant use of gold smalti adds a warm reflectivity to the picture plane, lifting the mosaic surface into an ethereal realm. “There is a quality about it that you can touch,” Kreilick says. “For me, it is a live material. It reflects and takes the light. This is something paintings can’t do.” The appearance of the surface changes from pale pastels with silvery highlights to deep earth tones with gold accents. As Kreilick explains, “When seen at different times of day or night under various kinds of lighting, it becomes different things, and takes on different facets. It becomes alive, in itself.”

Ms. Kreilick describes Forward as a depiction of Wisconsin’s drive to be a national leader, as invoked by drumbeats, pistons firing, and the pulsing rhythm of the piece. The geometries that appear so dense and abstract from an angle when entering the lobby, expand and elongate into identifiable topographies as we come to stand in front of the mural. We can discern specific landscape elements as we take in the whole scene: shimmering water, glacial formations, or a dense ancient woodland. It suggests Wisconsin in its process of formation, a panoramic view of deep geological time. Kreilick built upon the state’s pre-history by choosing a dynamic, organic, shape-language that spoke to Wisconsin’s economic thrust at mid-century.

Today, Wisconsinites are the fortunate beneficiaries of Marjorie Kreilick’s courageous vision. Ms. Kreilick is nearing 97 years old and her contributions to both the history of Wisconsin art and to the global tradition of mosaic are only beginning to be recognized. Through the efforts of mosaic specialist and co-author of this article, Lillian Sizemore, Kreilick’s studio papers have been acquired by The Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution and Kreilick’s teaching notes and lectures from her 38 years as a UW professor are now housed at the UW–Madison Faculty Archives. This institutional recognition underscores the national relevance of Kreilick’s work.

Many of the themes she introduced through her mosaic murals in the early 1960s are increasingly relevant today. Kreilick gave voice to ecological concerns more than a decade before the first Earth Day. She gave value to marginalized landscapes like wetlands, native prairies, and regional woodlands long before large land conservancies became active in Wisconsin. She embraced a pre-settlement vision of the Wisconsin landscape influenced by Native American ideas and traditions. She insisted upon seeing the Wisconsin landscape from an ecological perspective rather than an economic imperative. Through her creative independence and boundless energy, she continues to be an inspiration and a thinker who was ahead of her time. Kreilick’s work, especially her monumental mosaics in Milwaukee, hold important lessons for us and for future generations in our state and across the country.

The Future of Milwaukee’s Modernist Mosaics

These outstanding architectural artworks are nearing 70 years old. The mid-century mosaic at Rockwell Automation was recently cleaned and used as inspiration for a redesign of the employee cafeteria. Unfortunately, most of the other works documented here remain at risk. Leaders at the War Memorial Center have long fought historic designation. Chase Tower, like the War Memorial, has not been historically designated, and both the mosaics remain unprotected. In coming years, the State Office Building will be retired from active use. Land for a new State Office Building in Milwaukee has already been purchased. Saving monumental mosaics is no easy task—there are no straightforward solutions because each case is unique. That said, the fact remains that successful initiatives to preserve and restore mid-century mosaics are happening all over the world. Saving and re-purposing original buildings with the mosaics in situ is the best value proposition over the long term, and the most environmentally-sustainable solution in the short term.

These buildings are relevant in our historic landscape, and it is critical that each of them, with their monumental mosaics, be recognized for the unified vision of architectural art that makes them unique. To protect the legacy of these important Modern Movement buildings and their visionary, character-defining mosaics, we must move beyond appreciation into action so that future generations will have the opportunity to see and learn from these landmark creations.

About the Authors

Lillian Sizemore is an Italian-trained mosaicist, researcher, and educator with expertise in the twentieth-century mosaic movement. Her articles have been published internationally in Mosaïque, Andamento, Raw Vision, and Society for Commercial Archaeology. She holds a double degree in Fine Arts and Italian from Indiana University. She lives in Madison, WI, and is currently at work on the catalogue raisonné for Marjorie Kreilick.

Eric Vogel is a designer, educator, architectural historian, and former Chair of the 3D Design Department at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design. He holds a degree in Art History from Harvard University, a Master’s in Architecture from Southern California Institute of Architecture and is currently pursuing a mid-career PhD at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at UW–Milwaukee. He is Board President of the Wisconsin chapter of Docomomo-US and is working on a book entitled Milwaukee Moderns.