In late 2018, news spread that the church was closing and was slated to be sold to an undisclosed buyer. Rumors circulated that the buyer intended to demolish the church as the permissible zoning and value of land made the cost of renovation unattractive relative to new construction. Because the church was also a temporal outlier in the Lower Garden District’s period of significance (1850-1940), rehabilitation tax incentives were not available. The city’s Historic Districts and Landmarks Commission took the first step to preserve the building, quickly assembling a local landmark designation report that argued to protect the building on the basis of architectural and cultural significance. The Commission granted landmark status, ensuring that a developer could not raze the building without review.

As redevelopment discussions garnered public attention, a neighbor, Felicity Property, took an interest in the church. The real estate company was housed just across the street in an 1850s brick building with wrought iron galleries that was typical of Lower Garden District. Felicity had extensive experience both in redeveloping New Orleans’ historic buildings and completing new construction in urban infill lots. Founded by Tom Winingder, it was his three daughters that had the vision and drive to imagine the future of the church complex. Diana Fisher, Deborah Peters, and Kendall Winingder saw the potential to create a community-focused holistic health collective. Fisher had been diagnosed with breast cancer several years earlier at the young age of 34. She embarked on a healthcare odyssey, coordinating acupuncture, physical therapy, and meditation alongside conventional treatments provided by her oncologists. The fragmentation of care revealed a need in the local market: a healing space that could integrate the treatment of mind and body under one roof. Each sister brought a unique skillset to the table to realize the vision. Fisher had previously cofounded Tibetan House, a meditation and cultural center. Peters was the owner of a film equipment rental company and brought business acumen to the team. Winingder possessed years of experience working closely with development teams at the family business, where she served as creative director and in-house designer.

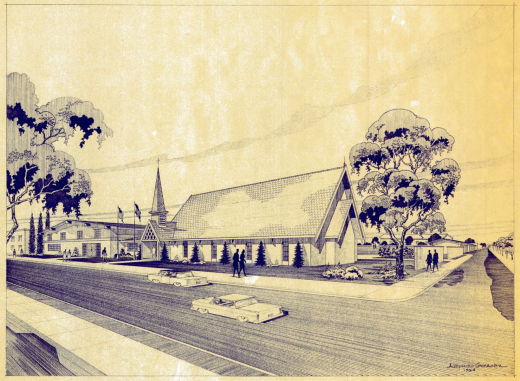

With Felicity Property’s expertise and backing, the sisters purchased the property and embarked on the renovation efforts. Inspections of the building and systems quickly made it clear that tax credits would be necessary to make the renovation financially viable. Because the church was outside the district’s period of significance, an individual listing nomination would be the path forward. Initial meetings with local and state officials proved supportive of the endeavor. Original construction documents were available and showed that the building was unchanged except for a slight modification to a rear interior staircase, retaining a high level of integrity.